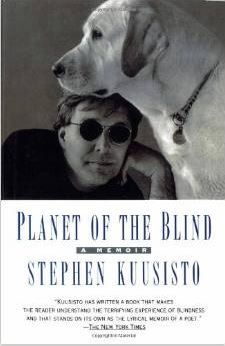

Do you remember receiving letters? They came in envelopes. Sometimes your fingers could feel despair through the paper—a strange packet with loopy scrawls. I’d published a book and the odd envelopes arrived like dolls with cramped little faces—things you’d have to spend time with certainly. Back then, twenty five years or so, I needed help with those letters and asked friends to read them to me. And so the voice of an acquaintance read lines roughly like these:

Dear Mr. Kuusisto. I’m going blind and I don’t want to live. The days have been hard and they’re getting so much harder. I have no idea how to stay in the world.

Or:

Dear Sir: I currently reside in prison. I was put here by a blind judge. He was a total bastard. Not all blind people are good. Thank you for reminding me there are some good ones…

When my sister was little she used to pop the heads off her dolls and carry those heads around with her, mostly by putting them in her pockets. I carried my own doll heads having written a book.

I knew there was this thing, the ether of literacy, a place where others read me and felt they might enter. Think of this as blogging with a stylus and sun dial. The internet is the ether for better or worse. Everyone knows about the “worse” of course. The better is small, carried in our pockets, occasionally brought into the light for examination. The doll heads. (When I first heard of the band “Talking Heads” I thought of my sister who used to hold up her Barbie skulls and have them speak.)

**

While reading Peter Gay’s Enlightenment, Volume 1 the following passage intrigued me. Gay is referring to his lifelong fascination with the Scottish philosopher David Hume, and in turn, the work of Stuart Hampshire:

“I was delighted to read Stuart Hampshire’s brief appraisal of Hume, “Hume’s Place in Philosophy,” in David Hume: A Symposium, 1–10, which accords precisely with my own estimate—an estimate I have arrived at after years of close and affectionate concern with Hume’s work. Hume, writes Hampshire, “defined one consistent, and within its own terms, irrefutable, attitude to politics, to the problems of society, to religion; an attitude which is supremely confident and clear, that of the perfect secular mind, which can accept, and submit itself to, the natural order, the facts of human nature, without anxiety, and therefore without a demand for ultimate solutions, for a guarantee that justice is somehow built into the nature of things. This philosophical attitude, because it is consistent and sincere, has its fitting style: that of irony …” (pp. 9–10). The demands and the possibilities of modern paganism have rarely been stated better than this.”

Excerpt From: Peter Gay. “Enlightenment Volume 1.” iBooks. https://itun.es/us/vuGqN.l

I’m fascinated by this wee passage. Gay’s admiration for Hume frames everything. Notice that he’s a delighted scholar! (Are scholars nowadays allowed to express their delight?)

Peter Gay is also an affectionate intellect. Adoration, devotion, and caring are critical to the life of the mind. (Have scholars forgotten this at their peril? One may well think so.)

What does Gay like so much? He likes an appraisal of Hume. Gay’s delight is doing the talking, and then, voila, he brings forward a paratactic delight—a tandem pleasure, Hampshire’s elegance, which is also in the service of Hume. Hume, who isn’t speaking. Here in a cloister of estimation are two scholars whose respective lives were devoted to ideas celebrating the nobility of a third. And the third is their father.

Notice the use of “attitude”. Talk about nuance! From the Latin for “fit” it was originally the proper word for placement, especially of figures in paintings. Later it became synonymous with stance. And once it entered the world of ideas it became the template for self-awareness. Attitude is valuable only insofar as it has the manners of irony.

I know of no better description of the contrarian intellectual. No anxiety, just the facts. So let’s say there is no God. Let’s say justice isn’t built into nature. What then? Why we get to build a confident and clear pagan democracy.

David Hume:

“Epicurus’s old questions are still unanswered: Is he (God) willing to prevent evil, but not able? then he is impotent. Is he able, but not willing? then he is malevolent. Is he both able and willing? then whence evil?”

“In our reasonings concerning matter of fact, there are all imaginable degrees of assurance, from the highest certainty to the lowest species of moral evidence. A wise man, therefore, proportions his belief to the evidence.”

**

These thoughts of a morning.

The pleasures of thought, the marvels of freedom.