A friend, characterizing a mutual friend said: “he has a mind like an unmade bed” and trust me that’s how I’m feeling. Of the unmade bed I recall an episode of the television version of “The Odd Couple” when Felix discovers a half eaten submarine sandwich in Oscar Madison’s bed. Oscar didn’t say it, but I will: “detritus ye will always have with ye” though one must surely admit when his defenses are down. I’m finding it difficult to concentrate.

This isn’t listlessness. It’s not the blues. (Though I know I’ve got them—a blind guy’s slumgullion of concerns from genetic testing of fetuses (rooting out probable disabled babies, think eugenics 2.0) to the race baiting narratives of American cleanliness espoused by the United States government and increasingly large parts of the industrialized world (Reich 4.0).

Or I worry about your mentally ill brother, child, mother, especially if they’re a person of color, for they’ll likely wind up dead or in jail in our clotted, Dickensian nation. Meanwhile the eroding middle class watches the Kardashians.

OK. Sorry. But when you’re an unmade bed, well, you become that man who natters on the bus. Some mornings I’m a single dendritic spark away from either mumbling or ranting.

My unmade bed is starting to smolder.

I’ve been on a lovely book tour which has taken me to Los Angeles, Santa Cruz, Calistoga, Denver, Richmond, and upstate New York. Talking with old acquaintances and new friends is a cleansing experience. I always meet good people on the road.

Check box: I’ve been talking to excellent human beings.

Check box: In Denver I got an Uber ride from a man who lectured me about the “end times” for twenty five minutes. He touched my hair. Said: “you’re already one of the saved. God loves you.”

Check: It’s raining in the airplane burial ground, as my friend Jim Crenner once wrote.

Crumbs from the bed…Marx was right about 40% of the time.

Bed: Antonio Gramsci was right about 80% of the time.

The above assertions are not incompatible.

Check: I’ve lately had several graduate students who don’t like to read and when pushed turn deflective and mean spirited. These are the children of “no child left behind” who’ve been trained for a decade to take tests. Confronted by the prose of Salman Rushdie they look at first perplexed, than hostile.

Crumb: The students mentioned believe they’re commodified, neutralized, oppressed, etc. according to their respective identities. They won’t read for strength. They believe ideology is strength. In this way they’re no more sophisticated than Donald Trump.

It’s a very hard time to be a professor.

Crumb: last night I realized for the 41,000th time that baseball won’t save me.

Check: I don’t care for popular music of any kind.

Ort. (Everyone’s favorite crossword bit)—scientists now believe outer space is filled with carbon molecules which they describe as “grease”—it means we’re essentially living in a vast kitchen drain.

Speck: The poet Donald Hall just passed. He was a good man on balance.

Note: I’m reading Dr King’s Refrigerator by Charles Johnson. Also: The Order of Time by Carlo Rovelli.

Speck: the thing about a book tour is you see with sufficient comic irony you’re not terribly important in the grand scheme.

Ort: I once introduced myself to the folk singer Utah Philips. Told him I was an anarchist at heart. He gave me a withering look. It said: “I’m the only god damned anarchist you little shit!”

What was it James Tate said? “No longer the perpetual search for an air conditioned friend….”

My step children are struggling to stay in the middle class.

I’ve a friend who’s lost his health insurance and has no job.

He doesn’t have the leisure for a mind like an unmade bed.

Like most halfway ethical beings I feel guilty.

Is sharing the unmade bed the best thing a writer can do?

That’s mostly what creative writing programs are all about.

The Finnish communist poet Pentti Saarikoski said: “I want to be the kind of poet who builds houses for people….”

Saarikoski was just kidding of course. The way poets do. He never built a house for anyone.

Is the unmade bed a place of ambition or escape. Is it both?

This is the point: I want to create unmade beds for everyone.

Check: we’d take turns being servants. The unmade bed mustn’t be class reserved.

What the hell am I talking about?

I fear for the life of imagination; what we used to call the life of the mind.

A student came to me not long ago and said he wanted to be a writer. Then he told me he hated reading.

I want to be a painter but I hate paint.

I’d like to cultivate my mind but not today.

Gramsci: “I’m a pessimist because of intelligence, but an optimist because of will.”

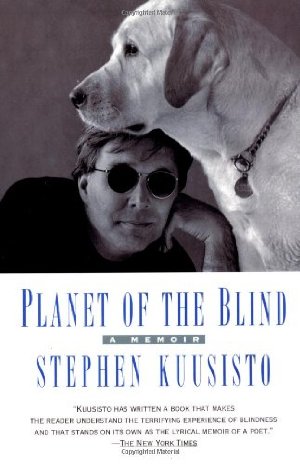

ABOUT: Stephen Kuusisto is the author of the memoirs Have Dog, Will Travel; Planet of the Blind (a New York Times “Notable Book of the Year”); and Eavesdropping: A Memoir of Blindness and Listening and of the poetry collections Only Bread, Only Light and Letters to Borges. A graduate of the Iowa Writer’s Workshop and a Fulbright Scholar, he has taught at the University of Iowa, Hobart and William Smith Colleges, and Ohio State University. He currently teaches at Syracuse University where he holds a University Professorship in Disability Studies. He is a frequent speaker in the US and abroad. His website is StephenKuusisto.com.

ABOUT: Stephen Kuusisto is the author of the memoirs Have Dog, Will Travel; Planet of the Blind (a New York Times “Notable Book of the Year”); and Eavesdropping: A Memoir of Blindness and Listening and of the poetry collections Only Bread, Only Light and Letters to Borges. A graduate of the Iowa Writer’s Workshop and a Fulbright Scholar, he has taught at the University of Iowa, Hobart and William Smith Colleges, and Ohio State University. He currently teaches at Syracuse University where he holds a University Professorship in Disability Studies. He is a frequent speaker in the US and abroad. His website is StephenKuusisto.com.

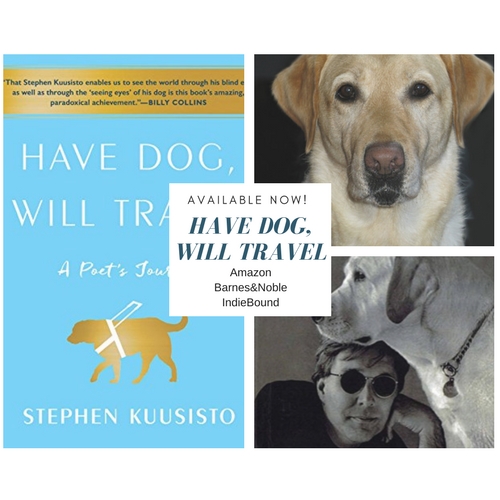

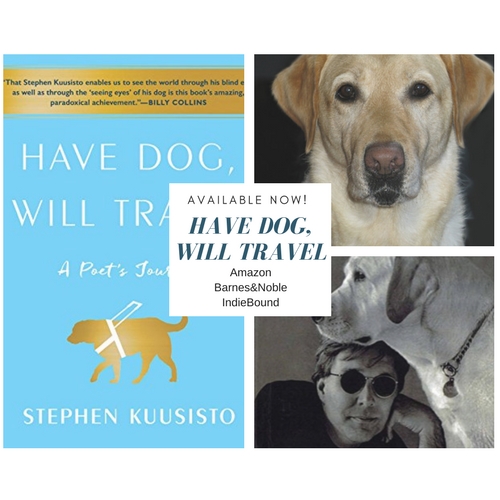

Have Dog, Will Travel: A Poet’s Journey is now available for pre-order:

Amazon

Barnes and Noble

IndieBound.org

(Photo picturing the cover of Stephen Kuusisto’s new memoir “Have Dog, Will Travel” along with his former guide dogs Nira (top) and Corky, bottom.) Bottom photo by Marion Ettlinger