While the GOP pushes its anti-unionist “right to work” narrative I think it’s high time the disabled steal the slogan. My global village remains unemployed. The right to work should be a matter of citizenship.

In their 2005 article “Corporate Culture and the Employment of Persons with Disabilities” Lisa Schur, Douglas Krusez and Peter Blanck raised a number of vital questions about business culture and disability: “What role does corporate culture play in the employment of people with disabilities? How does it facilitate or hinder their employment and promotional opportunities, and how can corporations develop supportive cultures that benefit people with disabilities, non-disabled employees, and the organization as a whole?”

(http://disability.law.uiowa.edu/lhpdc/publications/documents/BSL_JanFeb_2005/Corporate_culture.pdf)

One thing that really caught my eye in the article is this prodigious quote:

“When individuals with disabilities attempt to gain admittance to most organizational settings, it is as if a space ship lands in the corporate boardroom and little green men from Mars ask to be employed.”

—John, a 58-year-old employed man with paraplegia.

John, who I’ve not met, is my neighbor in the global village. If, like me, you’re disabled and have a job you’re automatically exceptional though the chances are good you’ll not feel that way. That is, once inside the workplace you’re still a little green man or woman. Meanwhile 6 out of 10 disabled people of working age remain jobless in the United States.

(https://www.brookings.edu/blog/the-avenue/2018/07/25/only-four-out-of-ten-working-age-adults-with-disabilities-are-employed/)

The Schur, Krusez and Blanck article highlights “the taken for granted beliefs” within corporate cultures:

“These ‘‘taken-for-granted beliefs’’ usually are unspoken and often unconscious. More formally, corporate culture at this level consists of a pattern of shared basic assumptions that the group learned as it solved its problems of external adaptation and internal integration, that has worked well enough to be considered valid and, therefore, to be taught to new members as the correct way to perceive, think, and feel in relation to those problems.”

The espoused values of the organization generally reflect what has worked in the past. Inviting green men and women into the community has not been a part of past practice.

**

Now the obstacles to change within organizations are considerable. Several years ago I came across a small pamphlet called Rejoicing in Diversity by Alan Weiss. The subtitle of the booklet was: “A Handbook for Managers on How to Accept and Embrace Diversity for Its Intrinsic Contribution to the Workplace”–-certainly a mouthful and perhaps not much of an advertisement. But I liked the word “rejoicing” and I also liked “intrinsic” for when you put these words side by side they speak of poetry. (The Chinese have two ideograms that stand together for poetry: a figure for “word” and a figure for “temple”). In any event, diversity in the workplace is seldom framed in ways that suggest spirit. Yet at the core of culture, spirit is all there is. Take away politics, real estate, the fighting over which end of the egg to crack and what you have left is the human wish for meaning. We tend to lose sight of this in Human Resources circles, substituting phrases like: Raising the Bar, Leadership, Assets, and the like. Talking about spirit is embarrassing. It’s like talking about the philosophers’ stone. Not even medieval historians feel comfortable talking about alchemy. You might look foolish. And we all know that the workplace should not be foolish.

I have advised many organizations on matters of disability and inclusion over the years. These opportunities came about because my first book of nonfiction was a bestseller and because for a time I was a senior administrator at one of the nation’s premier guide dog training schools. I had the opportunity to travel widely. Between 1995 and 2000 I visited 47 of the states in “the lower 48” and spoke at local, state, and federal agencies and public and private colleges. I have advised lots of blue chip organizations including the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Metropolitan Museum, the Kennedy Center, even resorts and hotels. Inevitably, wherever I have spoken I’ve heard the rhetoric of middle management: “empowerment”; “equal opportunity”; “productivity”; “zero tolerance”; “bias”; “sensitivity” and the like.

There is nothing wrong with these terms but to paraphrase Bill Clinton there’s nothing right about them either. And this is because the terms have no alchemy in them. They’re just nouns. Not all nouns have spirit inside them. The word “battleship” has no spirit but the word “blueberry” does. One of the first things a poet has to learn is that not all nouns are obedient to the soul.

Well meaning organizations (and some that may not be so) rely on the rhetoric of inclusion without imagining the opportunities for soul–and I mean “soul” the way Marvin Gaye would mean it: its what’s goin’ on. The human soul is present everywhere whether management acknowledges it or not. By way of analogy one can think of management as playing “battleship” while the soul is picking berries. Human souls are looking for ways to be fed and to be happy; management is often trapped in brittle or arid pronouncements.

Alan Weiss wrote:

“I have had the rather unique experiences of providing comprehensive reports to top-level executives on the acceptance of diversity in the workplace, only to have them shout, wide-eyed, “That’s not my company you’re describing!” Yet the feedback has been based on extensive focus group and survey work. Who’s wrong?

No one is wrong. What’s happened is that the respondents have reported what they are actually experiencing, I’ve conveyed that feedback accurately, and the executives are using their own intent and strategy as their frame of reference. The psychologists would call it cognitive dissonance–fully expecting one set of circumstances, while experiencing quite another.

The phenomenon at work is what I call the “thermal layer,” which is a management layer capable of distorting communications and directives it receives, turning them into something quite different. Managers in the thermal layer are the ones who actually control resources, make daily decisions and deal with the customer. They often have strong vested interests in preserving the status quo…think they have a better way of doing things, don’t trust senior management, don’t buy-into the strategy or, for whatever reasons, have some agenda of their own. “

Alan Weiss has perfectly described the breakdown that most often creates obstacles to true diversity and inclusion–or to use the language of the soul, communal berry tasting and picking.

For many years I’ve been asking folks at the universities where I’ve taught to take ownership of disability and accessibility and I have found a deeply invested thermal layer–a phenomenon I like to call the “Campus Rope-a-Dope” to borrow from Mr. Ali. The Campus Rope-a-Dope takes advantage of highly silo-ed administrative hierarchies to in effect pass the buck where disability and accessibility are concerned. Let’s be clear: no one wants to be identified as being part of the thermal layer just as no faculty member wants to be outed for being “dead wood”–and let’s also be clear that the person who persists in calling for blueberries when everyone else wants to talk about battleships will eventually be the victim of considerable distortion.

Alan Weiss again:

“Organizations seldom if ever fail in their intent, executive direction or strategy formulation. They fail in the execution and implementation of their initiatives. Nowhere is that more true than in the accommodation of diversity.”

For my own part I’ve called for universities to provide accessible bathrooms in buildings where I’ve taught. The struggles were astonishing. At the level of departmental administration, no one knows who’s in charge of these matters. That’s because the thermal layer is in charge. And the T.L. has a hundred silos. It also has committees.

I was once upbraided at the University of Iowa by someone from the human resources department. I’d been calling for the installation of assistive technology in the classrooms where I’d been teaching for over three years. The lack of compliance and communication around the issue had been comical and my method of handling it had been to bring my own talking laptop into each classroom and manfully wired it to the projection system–sometimes this worked and sometimes it didn’t. My every teaching experience was therefore a kind of gamble. No one was in charge. How was I upbraided? I was told that by calling attention to my difficulties with assistive technology compliance I’d done considerable damage to my reputation with the committee that handled disability issues–the point being that I’d apparently not gone through the proper channels in my requests for accommodations. This is how the thermal layer works. The thermal layer likes to deflect by distortion. And there were no proper channels.

Alan Weiss:

“How could anyone oppose an accommodating, equal-opportunity workplace?”

“Well, we know that some people can, sometimes with malicious motives, sometimes with prejudicial judgment, and sometimes because they perceive themselves to be adversely affected by the policies. You must be constantly on the watch for thermal zone reactions and distortions. If there’s a policy or value which causes conflict in the workplace, bring it to the surface and discuss openly. If there are misconceptions about policies, resolve them. The failure to do this doesn’t make the policies go away, it simply preserves the thermal layer until, like the executives above, the key decision makers get some shocking news. The reaction to that is usually worse than any other alternative, because senior management will try to legislate change rather than help people to embrace it.”

This brings us back to blueberries vs. battleships. The spirit of diversity vs. the demeaning of diversity initiatives through the employment of thermal language.

Because no one is really in charge when it comes to planning and implementation all disability accommodations are treated reactively and not proactively.

**

Workplace culture is a misnomer. Workplaces are generally affected by habits, old ones, and the thermal layer is where old patterns reside.

The green men and women are afterthoughts.

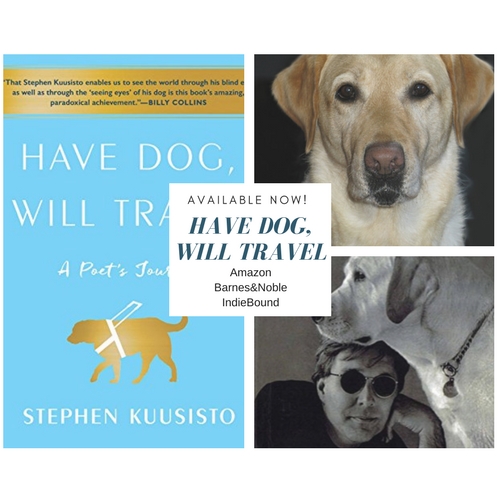

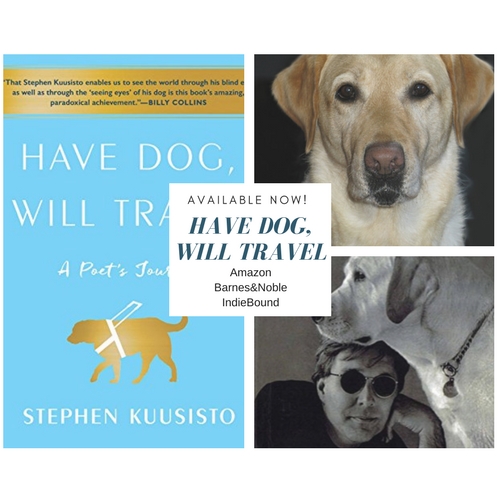

ABOUT: Stephen Kuusisto is the author of the memoirs Have Dog, Will Travel; Planet of the Blind (a New York Times “Notable Book of the Year”); and Eavesdropping: A Memoir of Blindness and Listening and of the poetry collections Only Bread, Only Light and Letters to Borges. A graduate of the Iowa Writer’s Workshop and a Fulbright Scholar, he has taught at the University of Iowa, Hobart and William Smith Colleges, and Ohio State University. He currently teaches at Syracuse University where he holds a University Professorship in Disability Studies. He is a frequent speaker in the US and abroad. His website is StephenKuusisto.com.

ABOUT: Stephen Kuusisto is the author of the memoirs Have Dog, Will Travel; Planet of the Blind (a New York Times “Notable Book of the Year”); and Eavesdropping: A Memoir of Blindness and Listening and of the poetry collections Only Bread, Only Light and Letters to Borges. A graduate of the Iowa Writer’s Workshop and a Fulbright Scholar, he has taught at the University of Iowa, Hobart and William Smith Colleges, and Ohio State University. He currently teaches at Syracuse University where he holds a University Professorship in Disability Studies. He is a frequent speaker in the US and abroad. His website is StephenKuusisto.com.

Have Dog, Will Travel: A Poet’s Journey is now available for pre-order:

Amazon

Barnes and Noble

IndieBound.org

(Photo picturing the cover of Stephen Kuusisto’s new memoir “Have Dog, Will Travel” along with his former guide dogs Nira (top) and Corky, bottom.) Bottom photo by Marion Ettlinger