I don't remember how old I was when I first heard about the injunction against shouting fire in a crowded theater. I think I was roughly eleven years old. Most of my cultural awareness coalesced in the fifth grade. That was the year I began reading the New York Times in earnest. My mother bought me a magnifier which allowed me to see newsprint with my one good legally blind eye. My eye jumped like a sparrow and words hopped about as I scanned them. Reading minus the ability to track left to right is almost impossible. But I kept at it. Despite grinding headaches and back spasms I read the news and learned about all manner of things. Don't shout fire unless its true. It was a good year for my moral development.

I've been writing for several days on this blog about a rapidly developing story concerning disability benefits and possible fraud. These stories have been poorly researched and I've been arguing that the topic of disability should require sophistication from reporters who choose to explore it. Because the stories now circulating are insufficiently informed, the reporting is sensational, driven by pathos (amped up emotion) rather than broader research. Note that I'm not talking about "balance" in reporting–let's agree that everyone who has a fifth grade education is opposed to fraud. Alright. We're in agreement. I'm not talking about balance. But I am talking about knowledge. As any seasoned reporter will tell you, knowing a subject guarantees a three dimensional article–as opposed to something that looks like propaganda. Even H.L. Mencken, one of the great polemicists of American journalism spent time talking to the locals when he was reporting the "monkey trial". In this case "talking to the locals" means speaking with scholars who actually study disability–I know many first rate public intellectuals who I could recommend to Public Radio International, NPR, Huffington Post, and now The Atlantic, just to name the most prominent outlets now spreading the story about disability benefits fraud.

The general premise of the articles now circulating comes from a Bloomberg report from May, 2012. In effect, Bloomberg's Alex Kowalski started the fire in the theater by reporting unemployment figures are declining because people who can't find jobs are giving up on work and collecting social security disability benefits. Mr. Kowalski's article explores the gray area, a sink hole really, into which older, often unskilled workers eventually tumble. In a country with an enormous service sector economy–one that requires manual dexterity and mobility, many physically impaired workers on unemployment find they can't easily return to work. Mr. Kowalski's article acknowledges this and seems to me altogether better researched than the pieces that have followed. What's "followed" leaves out what may be the largest fact in this sensational story–workplace accommodations for people with disabilities are brutally hard to obtain, often impossible to acquire, and largely depend upon a worker's ability to serve as a persuasive and unafraid self-advocate.

Since I began this post with a figure of speech, the "fire in a theater" let's say that reasonable accommodations are the "elephant in the room" whenever disability is the topic. Notice how I began this piece? I said my mother bought me a magnifier which allowed me to see newsprint when I was eleven years old. Nowadays I use a talking computer. My Macbook with "Voiceover" software is an accommodation. I know how to ask for it. I know my rights. I'm secure in my self-advocacy. But suppose I'm a garment worker. Suppose I'm losing my sight? Suppose I lose my job? Add to this that I never knew how to advocate for myself in the first place. You won't be returning to work. 70% of working age disabled people in the US remain unemployed. Why? Because potential employers don't want to provide reasonable accommodations. They fear theexpense, though in reality the expense for a typical workplace accommodation is negligible.

Disability is a hard scratch if you want to work. Once when I was unemployed having lost an adjunct teaching job I met with a counselor from the New York State Commission for the Blind. He said I’d never find another teaching job–blind people seldom get jobs anywhere–but he knew of a factory that made plastic lemons–they might be hiring people with disabilities–really, I ought to go there. I decided to go. The supervisor of the lemon factory took one look at me and said: "Gee, we just filled that position." The lemon stamper job would not be mine. Sticking with blindness and employment, a friend recently wrote me about a blind man with a guide dog who went to a jobs fair. He brought along a "hidden" sighted companion. This blind fellow gave his resume to several HR representatives and, in turn, his sighted friend watched discretely as they tossed the resumes in the trash. That's largely the way it is for job applicants with disabilities. Imagine the plight of older workers who have lost their physical capacities, who have no idea how to argue for help, and are without rehabilitation counseling of a high order. Who are the first people eliminated when companies are letting people go? Older workers. Age related disability is commonplace and accordingly the fact that the number of disability related social security applications has increased his not surprising. What "is" astonishing is the degree to which the journalistic outlets above have entered the subject of disability and employment without regard to the recent history of workplace accommodation denials. Successive Supreme Court rulings in the last decade have assured employers that they can quibble about the ADA's directives concerning employment flexibility for people with physical impairments. The ADA Restoration Act of 2007 was designed to offset several court decisions limiting the ADA's functions guaranteeing employment accommodations, but let's be clear, the landscape is still very difficult for older workers. What's particularly interesting in this cascading disability scam narrative is that Mr. Kowalski's original contention, that older people are in fact unlikely to find work once they lose physical functions, and that the numbers of people entering the SSDI rolls are not surprising–has been replaced by sensationalism, a matter that requires less analysis and seems to be popular.

Enter Jordan Weissmann's article at The Atlantic. Weissmann's article begins:

"Imagine for a moment that Congress woke up one morning, realized that the United States was suffering from a paralyzing long-term unemployment crisis, and, in a moment of progressive pique, decided to create a welfare program aimed at middle-aged, blue-collar workers. The one thing everybody could probably agree on is that it should help all those jobless 50-somethings find employment, right? Well, as NPR's Planet Money argues in an eye-opening story, it turns out there already is a "de facto welfare program" for those struggling Americans. The problem is, instead of getting the unemployed back on their feet, it pays them to give up work for good. I'm talking about Social Security's disability insurance program, which over 20 years has quietly morphed into one of the largest, yet least talked about, pieces of the social safety net. Since the early 1990s, the number of former workers receiving payments under it has more than doubled to about 8.5 million, as shown in Planet Money's graph below. More than five percent of all eligible adults are now on the rolls, up from around 3 percent twenty years ago. Add in children and spouses who also get checks, and the grand tally comes to 11.5 million."

The idea that there's a "de facto" welfare program that's geared toward fake disabilities plays well. But the story is only possible if the reporter leaves out several facts.

Fact: Disability is a social construction, not a medical matter. This means if you're physical condition prevents you from engaging in a major life activity–standing, walking, lifting, seeing hearing, thinking and processing information, speaking–the list is long–then you are eligible for social security disability payments, as long as you are unemployed "because of your disability". This is a very complex subject. The word disability comes down to us (in its modern sense) from Karl Marx who used it to describe laborers rendered unfit to work in the industrial economy. When we say disability is a social construction we mean, among other things that its co-determined by architecture, social attitudes, public education, the availability of accommodations, the flexibility of employers to provide workers with equivalent but different jobs–and most important of all, a progressive and inclusive cultural model. When these things are absent a person is disabled.

Fact: Over the past decade programs and services for people with disabilities have been shrinking not growing. People losing their vision find it harder to get orientation and mobility training or find access to assistive technologies. People with spinal cord injuries are getting less rehabilitation training and assistance than they received even a decade ago. A manual wheelchair costs around $12,000 and there are no programs providing financial assistance for manual wheel chair users. There are no credit or loan programs. Services have been in steep decline all over the nation.

Fact: Ableism (the unreflecting assumption that people with disabilities are deficient, incapable, maybe even dishonest) has been on the rise. In a nation that has long been known for blaming the poor for their plight, its not surprising that people with physical traumas are now being pilloried in the public square of journalism. Why not? We will tell our uninformed readership that people with disabilities on SSDI are planning to never work again. In fact, you can go off SSDI and return to the workforce. In fact there are programs in place to help people do just that. In fact people can go back to work if accommodations are provided.

Notice how Weissmann uses disability as a metaphor for the US economy. We're in a "paralyzing long term unemployment crisis"–this is a paratactic metaphor designed to frame a subtext which is purely ableist in its tenor. The figuration of Weissmann's piece is that real people want to get out of paralysis but there are people who are pretending to paralysis, don't you see?

Fact: From the earliest days of American film making, one of the most popular narratives was about people pretending to be disabled. Surely physical difference means something nefarious is going on. This idea still haunts the public nerve which is one reason the bizarre, unfeeling, sensation, neo-con reporting is gaining such easy traction.

Fact: The numbers of people going on social security disability are not up significantly.

Fact: There are regions of the country where, given the aging of the population, and the level of comparative poverty, the numbers of people with disabilities are going to be higher than one in five.

Fact: Employers have no incentives to create accommodating work places for people with physical impairments.

Weissmann writes that the increase in the numbers of disability claims under social security reflect a loosening of standards–that it got easier to claim you can't work during the last decade. His source? Economists.

Would you go to an economist if you wanted good information about dentistry? Why believe their analysis that there really aren't more physically impaired unemployed people nowadays?

Fact: The truth is, we don't know how many people with disabilities we really have. We have guesstimates, based on census modeling.

Fact: The census takers go from door to door in Baltimore and ask people if they can tell how many fingers they're holding up. If they can't tell, then they're blind. Simple.

Fact: There's competing evidence to Weissmann's statistical offering that the numbers of people who are limited because they don't have accommodations has indeed been rising. Disability is a matter of the constructed social and physical environment.

Fact: No major media outlets, not even progressive outlets cover disability issues in carefully analyzed ways–in point of fact they scarcely cover disability at all.

Fact: As we cut rehabilitation programs, foil the ADA, and fail to provide easy access to disability friendly education we create people with disabilities. Then we pretend they're crooks.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

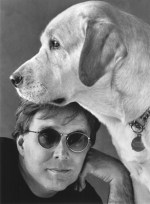

Professor Stephen Kuusisto is the author of “Eavesdropping: A Memoir of Blindness and Listening” and the acclaimed memoir “Planet of the Blind”, a New York Times “Notable Book of the Year”. His second collection of poems from Copper Canyon Press, “Letters to Borges“ has just been released. He is currently working on a book tentatively titled What a Dog Can Do. Steve speaks widely on diversity, disability, education, and public policy. www.stephenkuusisto.com, www.planet-of-the-blind.com

Professor Stephen Kuusisto is the author of “Eavesdropping: A Memoir of Blindness and Listening” and the acclaimed memoir “Planet of the Blind”, a New York Times “Notable Book of the Year”. His second collection of poems from Copper Canyon Press, “Letters to Borges“ has just been released. He is currently working on a book tentatively titled What a Dog Can Do. Steve speaks widely on diversity, disability, education, and public policy. www.stephenkuusisto.com, www.planet-of-the-blind.com