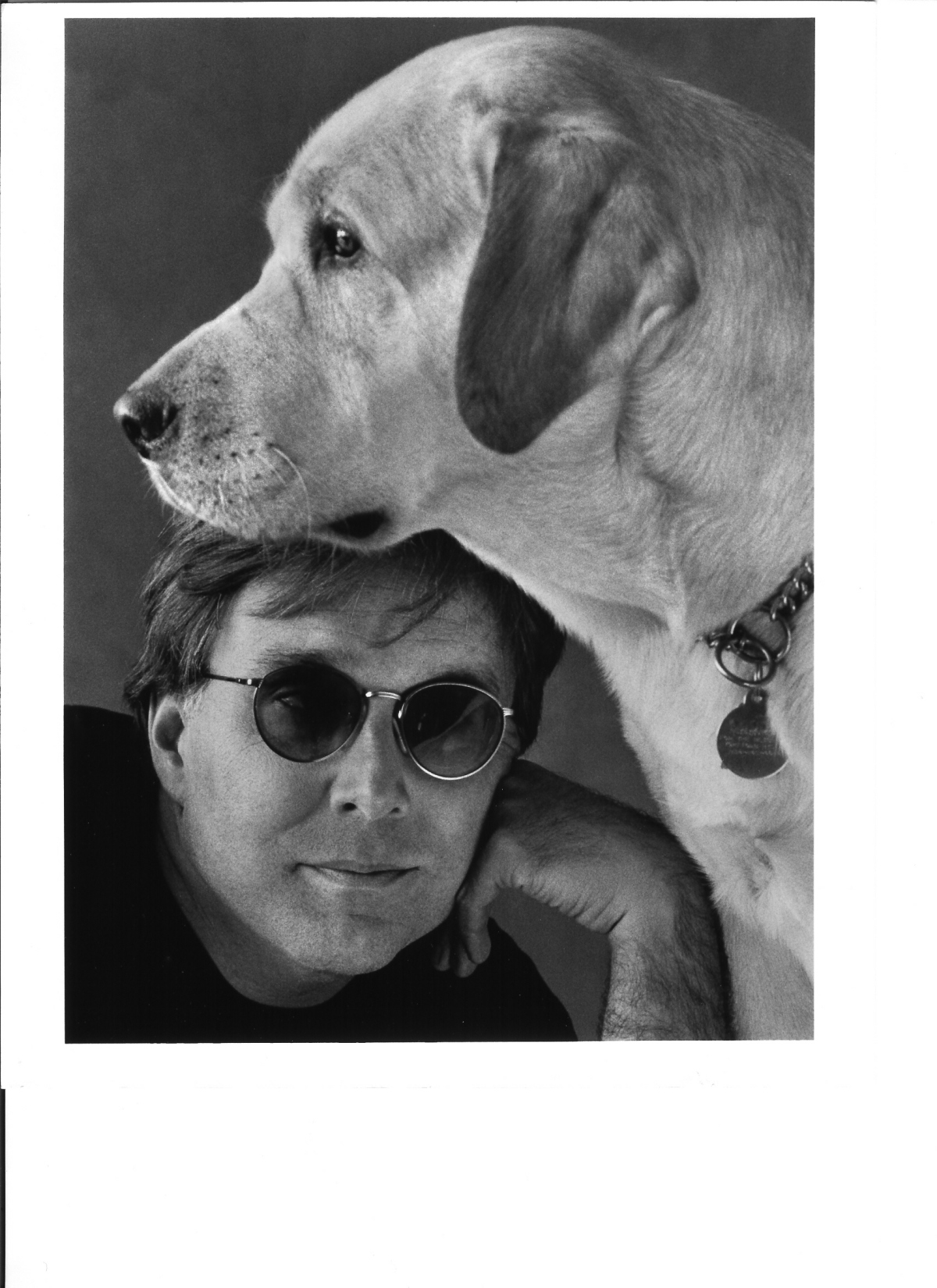

If you’re like me and you’ve a disability and you work in higher education you know that discrimination on the basis of physical difference is just as rampant from the left as the right. If you’re a faculty member who requires accommodations in the workplace you’re a nuisance. You might even be an embarrassment. I’ll never forget walking in a faculty procession with my guide dog and actually hearing a university trustee snicker as I passed. The chuckle wasn’t friendly and it spoke volumes. “Look! There goes our esteemed faculty! I always told you they didn’t know anything!” This happened at Syracuse University and yet it could have occurred on any campus. Disabled faculty are not the norm. Worse, we face bureaucratic delay and dismissive arguments when we bring up the inaccessibility of physical and digital spaces.

I submit it’s hard to avoid growing bitter. It’s hard to feel the very apparent lack of interest in disability discrimination even from faculty who hail from other marginalized positions. No one wants to imagine disability as being intersectional. Diversity and inclusion generally doesn’t include the cripples. Because this is so, the loneliness of being disabled in the faculty ranks is considerable. Ableism is a machine for isolation and deprivation. When you say, well people of color also have disabilities people look at their watches. The great liberal fiction is that universities are welcoming. All of this came to the surface for me this morning when I read about two black professors at the University of Virginia who were denied tenure. The academy does not welcome bodies of difference and while I’m not a person of color I can say I’ve seen the discriminatory daily routines “up close and personal” and I’m getting pretty close to being worn out.

Not so long ago I was called an “ignoramus” by a fellow faculty member who was snotty to me and my white cane. I know, it’s hard to believe. Of course It is never appropriate to call anyone an ignoramus in an educational setting for the term’s antonym s are “brain “ and “genius” and its synonyms include: airhead, birdbrain, blockhead, bonehead, bubblehead, chowderhead, chucklehead, clodpoll (or clodpole), clot [British], cluck, clunk, cretin, cuddy (or cuddie) [British dialect], deadhead, dim bulb [slang], dimwit, dip, dodo, dolt, donkey, doofus [slang], dope, dork [slang], dullard, dum-dum, dumbbell, dumbhead, dummkopf, dummy, dunce, dunderhead, fathead, gander, golem, goof, goon, half-wit, hammerhead, hardhead, idiot, imbecile, jackass, know-nothing, knucklehead, lamebrain, loggerhead [chiefly dialect], loon, lump, lunkhead, meathead, mome [archaic], moron, mug [chiefly British], mutt, natural, nimrod [slang], nincompoop, ninny, ninnyhammer, nit [chiefly British], nitwit, noddy, noodle, numskull (or numbskull), oaf, pinhead, prat [British], ratbag [chiefly Australian], saphead, schlub (also shlub) [slang], schnook [slang], simpleton, stock, stupe, stupid, thickhead, turkey, woodenhead, yahoo, yo-yo…

As a disabled person I know full well what the delegitimizing effects of language can do to anyone who hails from a historically marginalized background but where disability is concerned the labeling I’ve described has a particularly specious and ugly history. Idiot, moron, half-wit, dolt, cretin are all familiar to the disabled. One would expect relief from these terms at a university. What’s particularly galling is that the subject I was discussing with the professor in question was ableism—namely that I’d said hello to him on an elevator, I, a blind man with a white cane, and he simply stared at me. No acknowledgement. When two students got on the elevator he lit up and talked breezily about how he hates snow. I followed him to his office and said that by not acknowledging a blind person he creates a social dynamic that feels off-putting and I wanted to discuss the matter. He became instantly contemptuous.

Now of course that’s because of the synonyms above. In this man’s antediluvian world view the disabled really shouldn’t be in the academy. Ableism is not only more pervasive than people generally understand its also more consistent at universities than is commonly recognized.

As for me, I’m an ignorant man to professor “p” for that’s what I’m calling him. “P” for privileged.

He doesn’t know it yet, but incapacities likely await him.

Some day, long after I’m dead colleges and universities will be welcoming places for all. And disabled folks who are people of color will thrive. And yes blind people will not be laughed at.