I write in the mornings when the seeds of flowers are just ideas

The abiding chancel of our Sundays is an idea

My dog sits beside the desk liking middle distance

I jot a few phrases—up river, low sun

Think of Allen Ginsberg who once touched my shoulder

Category: poet

The methodological problem of how to be human…

—after Eeva Liisa Manner

Living demands action that works—see Aristotle up to his neck in water counting insects.

I don’t know you and cannot. Three circles this way, five crosses that way.

Have me you lilies; call me you blossoming meadow.

Ruminate, versify, grow flowers…

Early morning—I see how small my hands are,

What do I know about truth?

As a small child I loved the telephone

With its shell sounds

Others so far away…

No day after tomorrow, no tales

That couldn’t be right

And the bear of falsehood asleep in his forest.

Autumn is coming.

I’m not absolutely young anymore.

I was something. If I was I.

Please Mister, Stop Appropriating the Poor Cripples, Or, “The Blind Girl’s Sponge”

1.

A new novel appears; gets lots of praise; about a man who suffers a facial deformity and whatever passes for his inner life is destroyed. You guessed it: the author isn’t disabled. But he’s used a tried and true formula: deform a character and you can cover up your own literary deficiencies. Or nearly. Kafka understood this but his grotesqueries were about capitalism and not about individuals.

2.

In the airports, train stations, public byways, strangers approach and say unbidden things to me owing to my blindness. “I had a dog once,” they’ll say. Or: “I knew a blind girl once.” When I”m feeling charitable I think of their loneliness and let the intrusive moment go. When I’m more vituperative I’ll say anything to get out of the situation. “What dog?” I’ll say. Or: “I don’t like blind people.”

3.

You can only appropriate people you don’t understand. Notice I didn’t say, “insufficiently understand” because even maladroit and speculative thinking is better than incurious meddling. And that’s what ableist appropriation of disability is. Anthony Doerr has written a wholly fraudulent disabled character in his award winning novel “All the Light We Cannot See” (a title so stupid “that” alone should have killed it.) His charming blind girl can’t bathe herself though she’s something like fourteen. Her father (who is the author of course) has to help her. I think Doerr should have called the novel “The Blind Girl’s Sponge.”

4.

Now women writers do their own incurious meddling. There’s currently a very popular woman poet who writes of “grotesques” with enough whimsey to satisfy the ableist appetites of the creative writing academy. While I”m at it, let’s be clear that writers who hail from every kind of background write ableist junk. Feeling unimaginative? Just throw in a cripple or two. Two cripples will always be better than one. Beckett understood.

5.

“What’s the problem?” you say? “They’re just books.” You’re right. And Philip Larkin was right: “books are a load of crap.” And there’s more than one problem anyway. But Robinson Crusoe and Friday represent the unassailable comfort of appropriative culture. Novels are seldom progressivist. If you can get away with it, have three cripples in your coffee table book.

6.

In her new book “Believing in Shakespeare: Studies in Longing” Claire McEachern writes: “Even among person, plot, and place there exist differing expectations with respect to believability.” Her premise is that believing in characters is essentially a sacramental act. Read her book. It’s excellent. She writes:

“Persons are also found in nature as well as art; we can believe in each other, as well as in literary characters, the former suggesting the trust we confer on another ’ s purpose, the latter trust in an author ’ s conjuration. Sociobiology, anthropomorphism, and the sciences of empathy all suggest that humans are especially susceptible to each other; as philanthropic organizations know, a cause with a face is more difficult to shrug off than one without. 3 Prosopopoeia has long been the rhetorical figure employed to supernatural or political abstractions, endowing them with human-sized motive properties. Stories whose ultimate concern may be systemic or institutional identities or corporate fortunes (e.g., the fate of a nation, a race, or a culture) typically phrase their exempla in the unit of the individual. There is something particular about the person. Perhaps it is easier to believe in a literary person because less belief is required. People are people persons.”

7.

Prosopopoeia is just the thing, the ingredient you need if you want to turn real people into cartoons. Where disability is concerned Shakespeare was also a cultural appropriator. Caliban’s deformities come from Montaigne’s imagined ugly cannibals but no matter, you’ve got stock characters who will obediently and without controversy represent whatever imperial disdain you need to employ.

It has always been my contention that the first fully realized disabled character in Western literature is Melville’s Ahab. And though he’s not likable, he’s complex and understandable.

Which brings me back to my original point: the average ableist writer doesn’t need to know Ahab at all. He or she watches the cartoons.

I Live in No Country

I spent a dark month translating poetry in the far north and the poems followed me into sleep. Saarikoski’s snakes talked to my dream ears. I don’t always remember dreams but the snakes stayed with me. They followed me in the department store and came with me on the bus. I thought perhaps I should change my name to Asklepios. I also considered the bones inside the snakes. Those glassine springs with their electricities and appetites.

**

If you’re a reasonable woman or man or child you know you belong to no country.

This is the thing—poetry’s reification if you will—I belong in no room, no meeting, no tent.

**

The saddest poets are the ones who keep trying to put up a tent when there isn’t any rain in the forecast.

**

Walking early today thinking of Immanuel Kant, his a priori intuition and the elegance of reason. The snakes’ skeletons still following me down the street.

Disability Poetics, Essay Two

After the usual greetings….

Let’s talk about the up river blues, terror capitalism, how to live and what to do against a backdrop of Bram Stoker dread…I often imagine I’m closer to the gothic than many of my friends. Because I might die today stepping into traffic, blind, but with a dog for company. And I could die tomorrow in a strange hotel on my hands and knees trying to plug in an electric fan, dead too soon like Merton. And one must think about letting go slick phantasms in the buying and selling laundromat that is America, let go of the gruel thin lingo of political talk. Give away the early text books. Yes up river. Yes the blues. Yes a song or two about catfish.

The Planet That Would Have Me

It was Auden broke my heart then put it back together. Caruso followed with a love song from Naples. By the age of 8 I could read poems and listen alone to gramophone records. Blind I’d little street life though I pretended I belonged well enough in open air. Like most people who come from provinces I was happiest in my privacies, my attic with scratchy records and grey books. Though I could scarcely read that’s the world that would have me.

The ugliness of school was both a matter of being bullied for my disability and a curricular austerity. School never let me share what I was learning while alone. As a university professor these past thirty years I think of this. What do the students before me bring to the room? What can provinces teach us?

Provincial culture means the one we must create. Yeats couldn’t be Tennyson and though there were Irish poets before him, he had to be both cognizant of his inner life and the outward world. If he was going to be Irish-provincial he’d have to do it in a dual way. Its a matter of accomplishment that Yeats doesn’t quite fit anywhere. His planet doesn’t exist. Yet its apparent.

Is it a bit silly to invoke Yeats next to a kid with a large print book and a Victrola? I don’t think so. The inner life is Romanticism and strength of mind and each must find it in her or his way. You don’t have to be a poet to need your planet. More and more contemporary fiction and memoirs seek to find planets that will have us. Everyone hails from some version of my childhood attic.

I’m guilty of reductionism here. What I’m after is emergence not life alone with some arias. The planet that will have us is a made place and not granted. What is it made of? Yeats wrote:

By the help of an image

I call to my own opposite, summon all

That I have handled least, least looked upon.

The planet that will have you won’t look like you. Yeats knew and if we’re lucky we also learn it.

Yes when I go walking the world does not resemble my stride, my frame, nor, despite my yearnings for mysticism does the world answer my longings. The world simply is and not what I say of it.

The Blind Whale, Part One

I am inside the blind whale. I should say it isn’t Melville’s whale nor is it Jonah’s brute. The blind whale is made of all the dreams of sighted people occurring now and simultaneously. It is easier to say what the blind whale is not: it isn’t a prospect; it’s not a fortune; it’s not a standard nightmare. It isn’t of the left or of the right.

**

Now is the blind whale distinct from blindness itself? Yes. Genuine blindness is just a fish. A small one. A guppy. It swims in shallows. By distinction the blind whale cannot be seen. It’s a visual man’s phantasm. Or woman’s. Women are also screwed up by the blind whale.

**

Of course sighted people are terrified of blindness but this isn’t that. If the damned blind whale has significance beyond furnishing my roof it must be this: it’s composed of the oneiric afterthoughts of all visual humans. I do not mean repressed fears. Forget Freud and Jung. I mean the dropped car keys and lost buttons in dreams.

**

Petty detail is what the blind whale feasts on. The krill swims straight into the maw. What I mean is “sighted petty” —the blind spot in a rearview mirror.

**

I’m inside a non-fictive creature designed haphazardly by the small frights of the sighted. This is a problem.

**

When reading “Moby Dick” I’m always struck by what Melville doesn’t have to say. For instance he needn’t say that the intricate industrial-scientific butchery of a whale carcass is merely bloody psychoanalysis misunderstood. Nor does he have to say, “always remember what’s under the boat.”

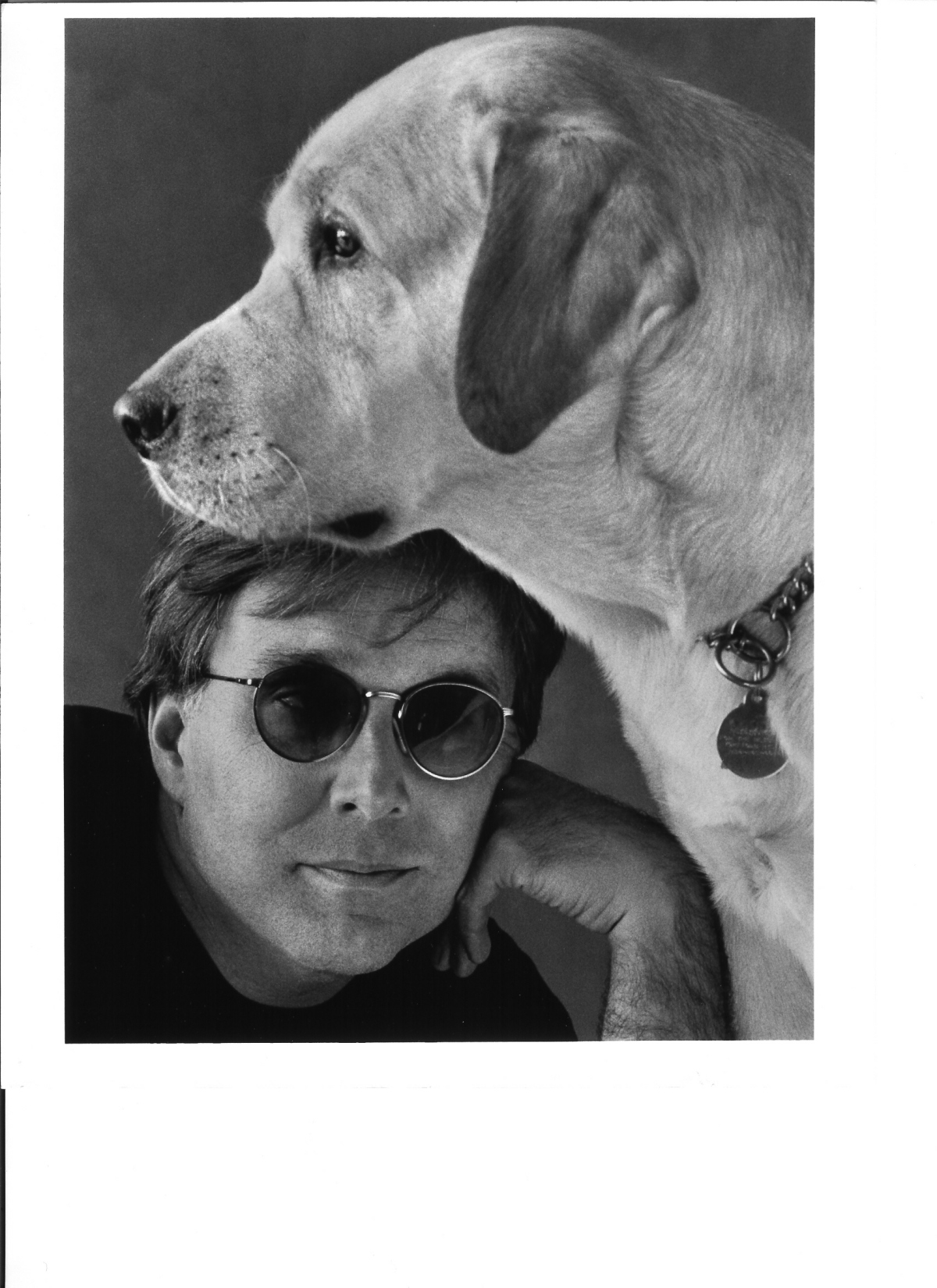

ABOUT: Stephen Kuusisto is the author of the memoirs Have Dog, Will Travel; Planet of the Blind (a New York Times “Notable Book of the Year”); and Eavesdropping: A Memoir of Blindness and Listening and of the poetry collections Only Bread, Only Light and Letters to Borges. A graduate of the Iowa Writer’s Workshop and a Fulbright Scholar, he has taught at the University of Iowa, Hobart and William Smith Colleges, and Ohio State University. He currently teaches at Syracuse University where he holds a University Professorship in Disability Studies. He is a frequent speaker in the US and abroad. His website is StephenKuusisto.com.

ABOUT: Stephen Kuusisto is the author of the memoirs Have Dog, Will Travel; Planet of the Blind (a New York Times “Notable Book of the Year”); and Eavesdropping: A Memoir of Blindness and Listening and of the poetry collections Only Bread, Only Light and Letters to Borges. A graduate of the Iowa Writer’s Workshop and a Fulbright Scholar, he has taught at the University of Iowa, Hobart and William Smith Colleges, and Ohio State University. He currently teaches at Syracuse University where he holds a University Professorship in Disability Studies. He is a frequent speaker in the US and abroad. His website is StephenKuusisto.com.

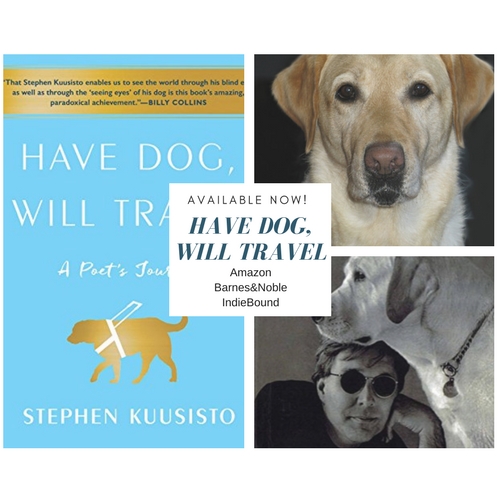

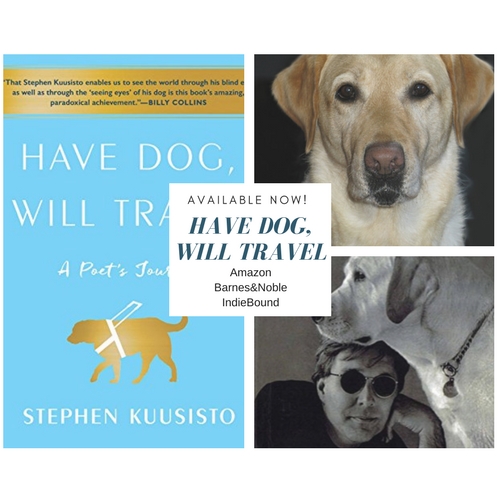

Have Dog, Will Travel: A Poet’s Journey is now available for pre-order:

Amazon

Barnes and Noble

IndieBound.org

(Photo picturing the cover of Stephen Kuusisto’s new memoir “Have Dog, Will Travel” along with his former guide dogs Nira (top) and Corky, bottom.) Bottom photo by Marion Ettlinger

I Can’t Tell You Who Lives Inside My Left Eye…

I can’t tell you who lives inside my left eye—

The better one which though blind

Has followed the parade all these years.

Is he bitter? Hungry? Does he laugh?

He reads weariness like a cipher.

He follows faint tracks of birds

Though he can’t see them.

This is to say he’s unreliable

But cunningly so

Fast in the mother-darkness.

The Poetry Conference

They see me walking with my stick or dog

And like a wisp of curtains

I hear their assumptions—

That I’ve been admitted by mistake

Or I must be lost

Surely poems require sight?

Screw Homer; who reads Milton?

Big time poets know blindness

Stands for something something—

Didn’t Rilke touch on it—

A blind man clutches a gray woman

And is lost forever in dark infancies?

That blind woman who writes verses—

She must be a bird

Something something

Maybe related to language

Her poems like feathers

Or yarrow stalks.

“How do you write so clearly

If you can’t see?”

“How do you read?”

“Would you have been a writer

If you had sight?”

“Can you see me at all?”

ABOUT: Stephen Kuusisto is the author of the memoirs Have Dog, Will Travel; Planet of the Blind (a New York Times “Notable Book of the Year”); and Eavesdropping: A Memoir of Blindness and Listening and of the poetry collections Only Bread, Only Light and Letters to Borges. A graduate of the Iowa Writer’s Workshop and a Fulbright Scholar, he has taught at the University of Iowa, Hobart and William Smith Colleges, and Ohio State University. He currently teaches at Syracuse University where he holds a University Professorship in Disability Studies. He is a frequent speaker in the US and abroad. His website is StephenKuusisto.com.

ABOUT: Stephen Kuusisto is the author of the memoirs Have Dog, Will Travel; Planet of the Blind (a New York Times “Notable Book of the Year”); and Eavesdropping: A Memoir of Blindness and Listening and of the poetry collections Only Bread, Only Light and Letters to Borges. A graduate of the Iowa Writer’s Workshop and a Fulbright Scholar, he has taught at the University of Iowa, Hobart and William Smith Colleges, and Ohio State University. He currently teaches at Syracuse University where he holds a University Professorship in Disability Studies. He is a frequent speaker in the US and abroad. His website is StephenKuusisto.com.

Have Dog, Will Travel: A Poet’s Journey is now available for pre-order:

Amazon

Barnes and Noble

IndieBound.org

(Photo picturing the cover of Stephen Kuusisto’s new memoir “Have Dog, Will Travel” along with his former guide dogs Nira (top) and Corky, bottom.) Bottom photo by Marion Ettlinger

Wittgenstein for Breakfast

From a Notebook circa 1990:

Comic irony: the condition of knowing what you didn’t know just seconds ago or years back and then, knowing how to think about it.

Tragic irony: the condition of not knowing the above while others do.

Morning irony: understanding you’ve the blues and knowing you’ll have to work with them all day.

Evening irony: seeing how the blues at 6 AM were correct or incorrect.

Luck stands between the above like an 18th century lamp lighter.

“What did the president know and when did he know it?” was not, as many believe, a political or juridical question, but one connoting either comic or tragic irony. Nixon is one of the few public figures to have had both. He knew he’d broken the law. He didn’t know quite how he came to be a law breaker. His answer, deflective, was to say “everybody does this….”

Whenever you hear someone say, “everybody does this,” remember the double tragic irony of not knowing which camp above you fit into.

I’ve always liked James Tate’s line: “curses on those who do or do not take dope.”

**

Memory

I loved my mother

She was always a such dark person

I see her everywhere in the woods

Muisti

Rakastin äitiäni

Hän oli aina tumma henkilö

Näen hänet kaikkialla metsässä

**

I guess there’s another category: forest irony. Where you recognize the animism of your subconscious.

**

I think of Ludwig Wittgenstein some mornings. Isn’t that odd? He occurs to me very early.

Usually it’s this quote that pops into my waking noggin:

“Death is not an event in life: we do not live to experience death. If we take eternity to mean not infinite temporal duration but timelessness, then eternal life belongs to those who live in the present. Our life has no end in the way in which our visual field has no limits.”

Oh I like this for lots of reasons. As a visually limited man I admire the temerity of the utterance, insofar as all humans have some kind of visual limitation. Wittgenstein posits the power of imagination to declare anything, and then, with a smear of logic, to cement an idea into consciousness. I suspect this is how he survived the trenches in WW I. And I know for certain its how the disabled survive. Look at the nouns:

Death. Event. Life. Experience. Eternity. Duration.

In my sophomore year of college I was fascinated by Boolean algebra. In mathematical logic, Boolean algebra is the “branch of algebra in which the values of the variables are the truth values true and false, usually denoted 1 and 0 respectively.” (See Wikipedia.)

The quote above is pure Boolean logic. One may easily draw a Boolean equation for the proposition eternal life belongs to those who live in the present. Then there’s a leap—Wittgenstein says our visual field has no limits.

If eternity = timelessness then the present (time) also equals timelessness. Good.

If timelessness is related to mindfulness (we take eternity to mean not infinite temporal duration) then the operations of mind become our vision. Hence our visual field (anyone’s) has no limit.

You can see where the poet in me would like this. You can see where the blind person in me also admires it.

As logic it is unimpeachable. The trick is to live it.

Early. Wittgenstein for breakfast.

ABOUT: Stephen Kuusisto is the author of the memoirs Have Dog, Will Travel; Planet of the Blind (a New York Times “Notable Book of the Year”); and Eavesdropping: A Memoir of Blindness and Listening and of the poetry collections Only Bread, Only Light and Letters to Borges. A graduate of the Iowa Writer’s Workshop and a Fulbright Scholar, he has taught at the University of Iowa, Hobart and William Smith Colleges, and Ohio State University. He currently teaches at Syracuse University where he holds a University Professorship in Disability Studies. He is a frequent speaker in the US and abroad. His website is StephenKuusisto.com.

ABOUT: Stephen Kuusisto is the author of the memoirs Have Dog, Will Travel; Planet of the Blind (a New York Times “Notable Book of the Year”); and Eavesdropping: A Memoir of Blindness and Listening and of the poetry collections Only Bread, Only Light and Letters to Borges. A graduate of the Iowa Writer’s Workshop and a Fulbright Scholar, he has taught at the University of Iowa, Hobart and William Smith Colleges, and Ohio State University. He currently teaches at Syracuse University where he holds a University Professorship in Disability Studies. He is a frequent speaker in the US and abroad. His website is StephenKuusisto.com.

Have Dog, Will Travel: A Poet’s Journey is now available for pre-order:

Amazon

Barnes and Noble

IndieBound.org

(Photo picturing the cover of Stephen Kuusisto’s new memoir “Have Dog, Will Travel” along with his former guide dogs Nira (top) and Corky, bottom.) Bottom photo by Marion Ettlinger