By Ralph James Savarese

It’s a rare day when someone publishes a book in the subfield that only you and a few other scholars work in. The University of Michigan Press has just released Julia Rodas’s Autistic Disturbances: Theorizing Autism Poetics from the DSM to Robinson Crusoe (with a fine preface by Melanie Yergeau). It’s an important book that makes significant contributions to the study of autistic language in the humanities and, in particular, literature. For one thing, it adds to the project of critique that is at the core of critical autism studies, aggressively countering the impulse to pathologize neurological difference. It does so by ingeniously revealing the extent to which literature, a prized form of cultural expression, relies heavily on linguistic features that, in another context—namely, medicine and science—are marshalled to demonstrate impairment in autism. As Rodas writes in the introduction, “This book recognizes echoes, tones, patterns and confluences between autistic language, which is typically devalued…, and language used in culturally valued literary texts.” “Pointing to the existence of an autistic expressive fingerprint,” she seeks to give autistic utterances, like a pair of scuffed shoes, a new contextual shine.

Rodas begins by presenting the writings of Elaine C. These writings, one of “the earliest published expressions of a professionally recognized autist,” appear in Leo Kanner’s landmark 1943 study, whose title, “Autistic Disturbances of Affective Contact,” Rodas redeploys to great effect.

“Dinosaurs don’t cry”; “Crayfish, sharks, fish and rocks”; “Crayfish and forks

live in children’s tummies”; “Butterflies live in children’s stomachs, and in

their panties, too”; “Fish have sharp teeth and bite little children”; “There is

war in the sky”; “Rocks and crags, I will kill” …; “Gargoyles bite children and

drink oil”; “I will crush old angle worms, he bites children” …; “Gargoyles have

milk bags”; “Needle head. Pink wee-wee. Has a yellow leg. Cutting the dead

deer. Poison deer. “Poor Elaine. No tadpoles in the house. Men broke deer’s

leg” …; “Tigers and cats”; “Seals and salamanders”; “Bears and foxes.”

This young woman’s language not only disturbs but also “challenges ordinary communicative expectations,” Rodas claims. “It repeats and ricochets, suggesting a potential listener beyond the clinical recorder.” Elaine’s words are “striking and forceful and beautifully, queerly concentrated…, a profound achievement of repetition, order and chaos.” In short, they are much more like a modernist (or postmodernist) poem than ostensibly pointless, solipsistic babble.

And yet, the focus of Rodas’s book isn’t such utterances themselves. As she says explicitly, “My project asks not about autistic authorship, but about autistic text, and it imagines autistic voice as a widespread and influential aesthetic, with distinctive patterns of expression…running through an array of texts, sometimes broadly visible and in other instances as a fine thread.” Rodas wisely avoids the rather common, and perversely diagnostic, gesture of finding autistic characters in literature or of sniffing out autistic proclivities in authors. Instead, she fixes her attention on the way that literature behaves, the way that it eschews strictly utilitarian forms of communication in favor of something more indirect, formally resonant, and mischievous. The effect of her argument is less to undermine a sense of autistic identity (either neurological or cultural)—she’s not saying that anyone can be autistic—than to establish a correspondence between distinctive orientations to language. And so, we’re treated to marvelously inventive and subtle readings of Andy Warhol’s The Philosophy of Andy Warhol: From A to Be and Back Again, Charlotte Bronte’s Villette, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, and poems by Raymond Carver, David Antin, and Georges Perec. Even the DSM (the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) is found to be autistic, what with its commitment to—nay, its perseverative obsession with—listing and systematizing.

The significance of this move—showing that nearly every purported defect in autistic language use finds its corrective match in literature—cannot be overstated. For more than a decade, I have been arguing in my own work that literature, especially poetry, constitutes a kind of linguistic haven, a place of neurocosmopolitan hospitality, and I have devoted myself to teaching creative writing to aspiring autistic writers.1 Yet even more important than such training is the book’s implicit recognition that autistics bring the literary to everyday linguistic encounters. I will never forget my autistic son, DJ, typing one afternoon on his text-to-voice synthesizer, “Why don’t you all [meaning, nonautistics] use language creatively when you’re doing simple things?” He meant, for example, asking for a glass of water or reporting on the day’s events. He found most neurotypical language flat and boring, without any sensuous appeal. (Literature for neurotypicals is like a zoo—the literary kept largely in its effete cage.) If DJ wanted a glass of water when he was young, he was apt to say something like, “Thirst floats in the tiny aquarium” or “Tongue tongue tongue needs a bath.”

Imagine if medical professionals were compelled to read Rodas’s Autistic Disturbances, if training in literary study could improve patient-doctor encounters, to say nothing of parent-child or teacher-student encounters. Listen to how Rita Charon explains the value of “narrative medicine”:

What narrative medicine offers…is a disciplined and deep set of conceptual

frameworks—mostly from literary studies, and especially from narratology—

that give us theoretical means to understand why acts of doctoring are not

unlike acts of reading, interpreting and writing and how such things as reading

fiction and writing ordinary narrative prose about our patients help to make

us better doctors. By examining medical practices in the light of robust

narrative theories, we begin to be able to make new sense of the genres of

medicine, the telling situations that obtain, say, at attending rounds, the ethics

that bind the teller to the listener in the office, and of the events of illness

themselves.

Charon presumes a (largely) neurotypical patient, but we don’t have to, and her focus is narrative. We might speak of poetic medicine and imagine similar reforms. As Dora Raymaker and Christina Nicolaidis have demonstrated repeatedly, access to adequate healthcare continues to be a significant problem for autistics. Appropriately trained, a doctor might know how to receive a remark such as Elaine C.’s “Butterflies live in children’s stomachs, and in their panties, too.” Is the girl referring to anxiety, which is a huge challenge in autism? Or maybe to puberty and the changes it brings? She does refer, after all, to “pink wee-wee.” What if the doctor’s opening gambit were something like:

Thou spark of life that wavest wings of gold,

Thou songless wanderer mid the songful birds,

With Nature’s secrets in thy tints unrolled

Through gorgeous cipher, past the reach of words,

Yet dear to every child

In glad pursuit beguiled,

Living his unspoiled days mid flowers and flocks and herds!2

Or even better, this poem by the above poet’s now infinitely more famous and reclusive correspondent:

A Bird, came down the Walk –

He did not know I saw –

He bit an Angle Worm in halves

And ate the fellow, raw,

And then, he drank a Dew

From a convenient Grass –

And then hopped sidewise to the Wall

To let a Beetle pass –

He glanced with rapid eyes,

That hurried all abroad –

They looked like frightened Beads, I thought,

He stirred his Velvet Head. –

Like one in danger, Cautious,

I offered him a Crumb,

And he unrolled his feathers,

And rowed him softer Home –

Than Oars divide the Ocean,

Too silver for a seam,

Or Butterflies, off Banks of Noon,

Leap, plashless as they swim.3

Autistic Disturbances is a splendid book, but I would be remiss if I didn’t quibble with something. (That, after all, is what academics do!) Rodas is far too defensive about her decision to focus on classic literary works instead of autistic memoirs. Anxiety about identity politics, about appropriating autism, finding it everywhere but in the published works of autistic authors, compels her to mount a number of less than credible justifications for her decision. At one point, she claims, “So much autism memoir presents a strangely nonautistic vibe.” She sweeps aside a long and varied list of autistic life writers with arguments about market expectations (“the requirements of publishing”) and a push toward normalcy (“rhetorical colonization”). “Geared as the genre is to audiences that are overwhelmingly neurotypical and vetted by publishers with an interest in commercial sales, autistic autobiography,” Rodas argues, “typically adopts surprisingly commonplace rhetoric and language, effectively translating autistic experience and identity into largely conventional terms.”

I would strenuously object to this sweeping generalization, even as I concede the impact of these very real pressures. The work of Tito Mukhopadhyay, Dawn Prince, Donna Williams, Larry Bissonnette, and Ido Kedar, to name just a few autistic writers, is more than sufficiently autistic to shoulder the search for literary autism. Prince and Williams, two authors whom Rodas explicitly dismisses, may not line up perfectly with the rhetorical features that she emphasizes, but they evince others—others that I would foreground, such as a wild lyricism and a deeply synesthetic understanding of distinction and relation. Moreover, both Prince and Williams, after finding initial commercial success with their first books, went on to write subsequent books that were published by smaller, independent presses. These books are quite quirky and literary.

One real danger in claiming that autistic memoir isn’t autistic enough is that it leaves no room for autistic development, for complete immersion in the world. According to this framework, either you’re Elaine C. or Richard M., linguistic spectacles deprived of an education and accorded no life opportunities (let alone civil rights), or you’re Raymond Carver or Daniel DeFoe, recognized artists. The cost of what I call a neurocosmopolitan or (hyrbrid) identity can’t be the loss of “autistic voice” or, worse, a devastating, socially imposed “aloneness.” We’re all acculturated. Nonautistic poets lose the elastic language of childhood and then, as adults, recover some portion of it in their work. Better to imagine, for those autistics who seek to be writers, the possibility of capitalizing on a potential literary advantage. Otherwise, we’re practicing a romantic and uncritical primitivism.

And anyway, I’m not convinced that autistics entirely lose their linguistic difference when they’re included in life and publishing. Once, in the midst of an interview with Tito Mukhopadhyay, I spoke of his fondness for the trope of personification, and he forcefully interrupted me, typing, “It shall be called pan-psychism by me!” He rejected the easy domestication of his vital engagement with non-human entities. It wasn’t a conceit, or, rather, his conceits were so much more than mere conceits. When I looked more closely at his work, I realized that I had reduced what I read to what was familiar to me. Said another way, Mukhopadhyay was simply using the tools at hand, the way someone fluent in a second language might use them: with great skill but also with a difference.

One final quibble. Rodas’s chosen texts—she says that she could have picked other ones—have the unfortunate effect of reinforcing the idea that autism is a “white” disorder. She analyzes no works by writers of color. An ungenerous reading of Autistic Disturbances might claim that a universal “autistic voice” is speaking here—universal, as in a privileged white voice that includes everyone while elevating itself and effacing all difference. Yet that critique would be unfair, or at least incomplete. Rodas hasn’t worked out the implications of a transhistorical autistic “fingerprint.” Does neurology trump culture and all other identity positions? Does it trump unique literary traditions? She’s generalizing about autism, and she’s generalizing about literature: each marks a linguistic departure from the norm, and each seems to reflect the other. The next step, in this tremendously illuminating project, is to introduce the concept of intersectionality. How might autism interact with the myriad other pressures and influences to which it is subjected? And how might we welcome that interaction?

1See “What Some Autistics Can Teach Us about Poetry: A Neurocosmopolitan Approach,” https://www.academia.edu/6347978/What_Some_Autistics_Can_Teach_Us_about_Poetry_A_Neurocosmopolitan_Approach?auto=download; see “I Object: Autism, Empathy, and the Trope of Personification,”

https://www.academia.edu/6428705/I_Object_Autism_Empathy_and_the_Trope_of_Personification; see “The Critic as Neurocosmopolite: What Cognitive Approaches to Literature Can Learn from Disability Studies,” https://www.academia.edu/7788443/_The_Critic_as_Neurocosmopolite_Or_What_Cognitive_Approaches_to_Literature_Can_Learn_from_Disability_Studies_Lisa_Zunshine_in_Conversation_with_Ralph_James_Savarese_Narrative_2014_.

2“Ode to a Butterfly,” Thomas Wentworth Higginson

3”A Bird, Came Down the Walk,” Emily Dickinson

Ralph James Savarese

Grinnell College

Ralph James Savarese is the author of Reasonable People: A Memoir of Autism and Adoption and the coeditor of three collections, including the first on the concept of neurodiversity. In October, Duke University Press will publish his new book, See It Feelingly: Classic Novels, Autistic Readers, and the Schooling of a No-Good English Professor.

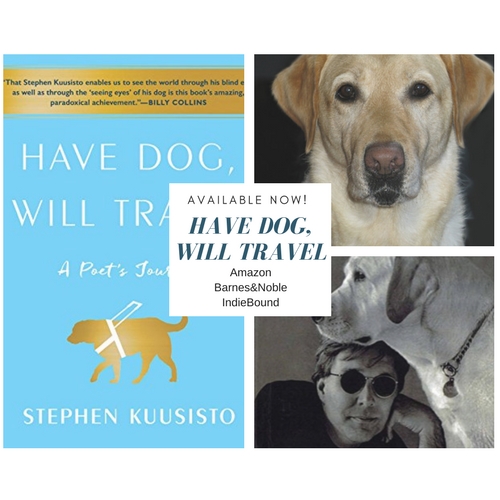

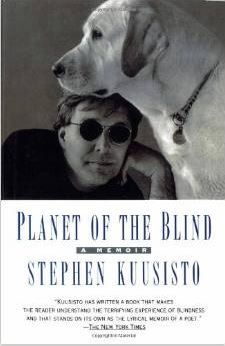

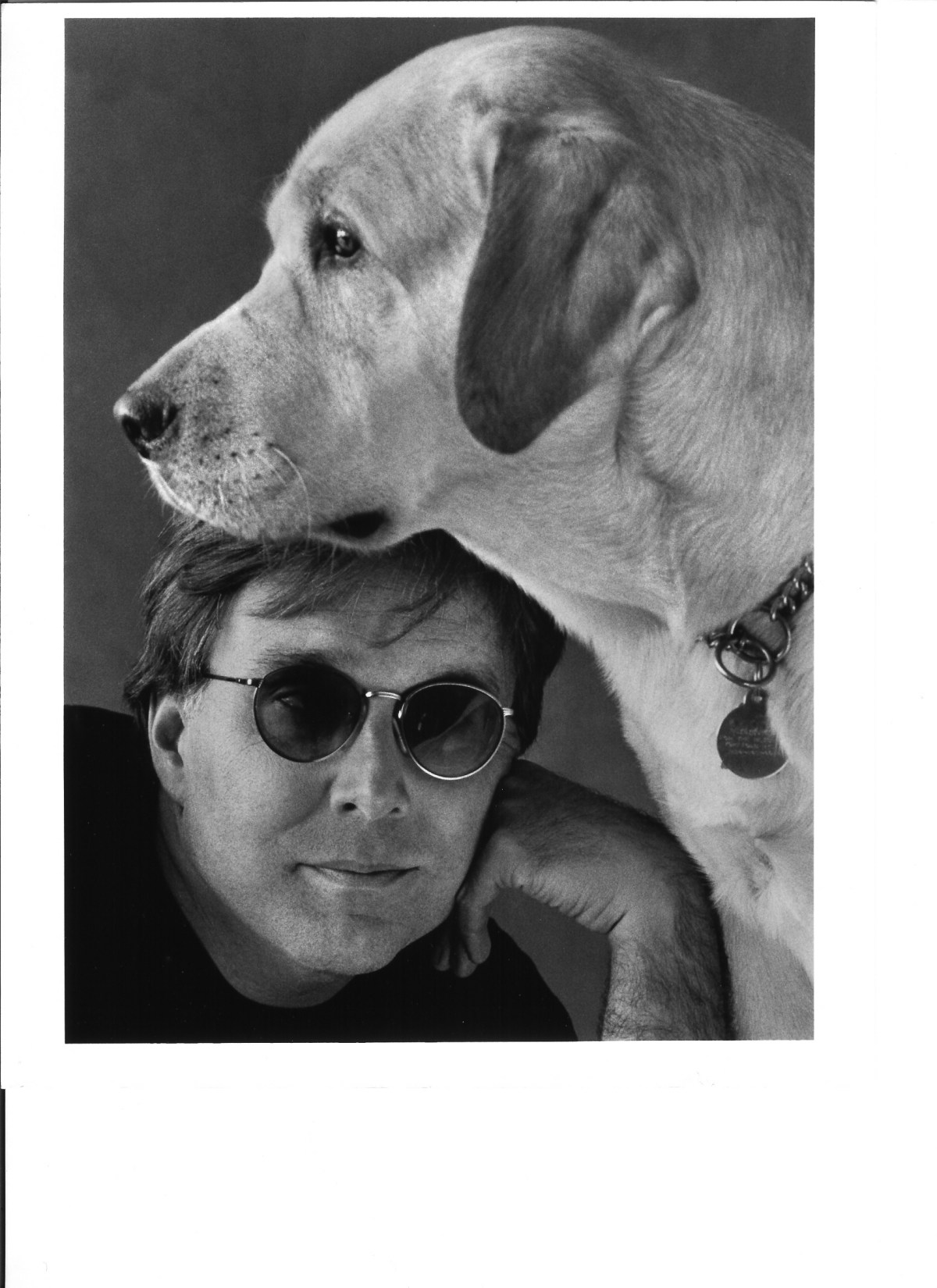

ABOUT: Stephen Kuusisto is the author of the memoirs Have Dog, Will Travel; Planet of the Blind (a New York Times “Notable Book of the Year”); and Eavesdropping: A Memoir of Blindness and Listening and of the poetry collections Only Bread, Only Light and Letters to Borges. A graduate of the Iowa Writer’s Workshop and a Fulbright Scholar, he has taught at the University of Iowa, Hobart and William Smith Colleges, and Ohio State University. He currently teaches at Syracuse University where he holds a University Professorship in Disability Studies. He is a frequent speaker in the US and abroad. His website is StephenKuusisto.com.

ABOUT: Stephen Kuusisto is the author of the memoirs Have Dog, Will Travel; Planet of the Blind (a New York Times “Notable Book of the Year”); and Eavesdropping: A Memoir of Blindness and Listening and of the poetry collections Only Bread, Only Light and Letters to Borges. A graduate of the Iowa Writer’s Workshop and a Fulbright Scholar, he has taught at the University of Iowa, Hobart and William Smith Colleges, and Ohio State University. He currently teaches at Syracuse University where he holds a University Professorship in Disability Studies. He is a frequent speaker in the US and abroad. His website is StephenKuusisto.com.