I must admit I’m a cranky man. This means I’m a hurdy gurdy man, a street nuisance. Did you know most curbside organ players were disabled? Many were war veterans. Jobless. They played for your amusement. Several cities in America didn’t like them. “Ugly Laws” were adopted across the nation at the turn of the last century—edicts stipulating bothersome, unsightly people were forbidden to appear in public. This was excellent news for the asylum business. The United States loves to lock people up for any reason at all—you’re black and deaf. Asylum. You’re blind. Asylum. You’re an immigrant in Trump’s America. Instant prison camp. Native American. Home detention. Gay? The Asylum. The Los Angeles County Jail is the largest psychiatric facility in the U.S. Cranky? You bet. I’m so cranky I can’t muster irony.

Disabled I know a good deal about cruel irony—“the act of using somebody’s words against them, usually when something to their great detriment is about to be inflicted upon them.”

I’ll never forget an administrator of a certain college who, once he had me behind a closed door told me I wasn’t a competitive blind person, why he had a roommate at university who was a blind Olympic rower and so forth. He was essentially firing me because I’d asked for a reasonable accommodation.

But you see here’s the trap. I’m cranky if I talk back, assert my dignity and my rights. I am especially cranky at the University where when I ask for basic ADA 101 accommodations, (a sighted graduate assistant to help me in my daily work) accessible texts, descriptions of overhead projections, asking that our websites and teaching software be accessible and so forth) I’m labeled as a real cranky pants. Academic ableism is built on cruel irony. “If you were more like us you wouldn’t have a problem. You don’t like what’s happening to you? You must be the problem. Not us. Not us able bodied birdies….”

I’ve met so many able bodied birdies. They may have different kinds of feathers but their song is always the same.

Ableism, the experience of it, requires the French adjective écœurante —for disability discrimination is simultaneously heartless and sickening. I recall the professor of English at the University of Iowa who told me my blindness would preclude me from being in his “famous” graduate class on Charles Olson. Another professor snickered when I said I was reading books on tape. When I protested the chairman of the English department told said I was a whiner and complainer. I wept alone in the Men’s room. My path forward to a Ph.D. in English at the University of Iowa was stymied. This was a full six years before the ADA was signed into law. Who was I to imagine a place at the agora’s marble stump?

Now I had an MFA degree from the creative writing program at that same university and I just went ahead and wrote books and sometimes appeared on radio and television and I wrote for big magazines and over time I received tenure at The Ohio State University. Later I went back to teach at Iowa despite my earlier experience and these days I’m at Syracuse. I’m a survivor of sorts. I’m a blind professor. The odds were never in my favor. Somewhere along the way I began thinking of Moliere in my private moments and I laughed because after all, every human occasion is comical and Moliere recognized the comedic types one encounters in closed societies better than anyone before or since.

It doesn’t really matter what institution of higher education you’re at, if you’re disabled you’ll meet the following Moliere-esque figures. The heartless and sickening ye will always have with ye if you trek onto a college campus. You’re more likely to spot them first if you hail from a historically marginalized background however, the ecoeurantists are more prone to blab at you if you’re disabled, especially behind closed doors. Ableists love closed doors. All bigots love closed doors.

The “Tartuffe” is an administrator, usually a dean or provost who will tell you with affected gestures that he, she, they, what have you, cares a great deal about disability and then, despite the fact a disabled person has outlined a genuine problem, never helps out.

The “Harpagon” is also an administrator, but he, she, they, can also be a faculty member. The Harpagon is driven by rhetorics of cheapness. It will cost too much to retrofit this bathroom, classroom, syllabus, website, etc. If the Harpagon is a professor he, she, they, generally drives a nice car.

Statue du Commandeur: a rigid, punctilious, puritanical college president—“this is the way we’ve always done it. If we changed things for you, we’d have to change things for everybody. Yes, it certainly must be hard…” See:

The Geronte: when his son is kidnapped he says: “Que diable allait-il faire dans cette galère?” (What in the deuce did he want to go on that galley for?” In other words, he brought this upon himself. “Really, shouldn’t you try something easier? I could have told you.”

These are the principle types of ableists. I invite you to add your own.

The one thing they have in common besides a privileged and thoroughly unexamined attachment to the idea that education is a race requiring stamina and deprivation, is that they all genuinely believe that accommodations are a kind of vanity.

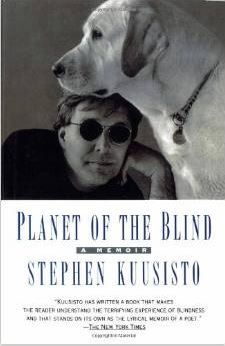

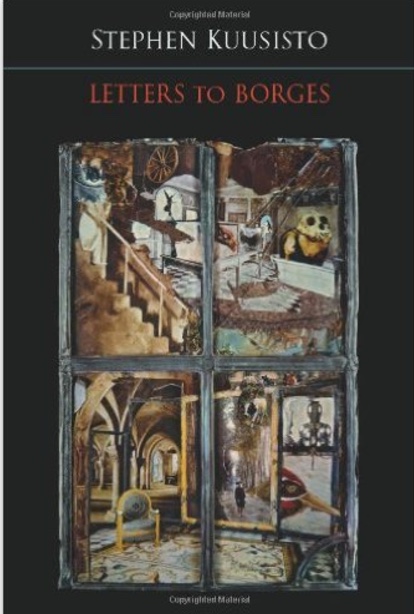

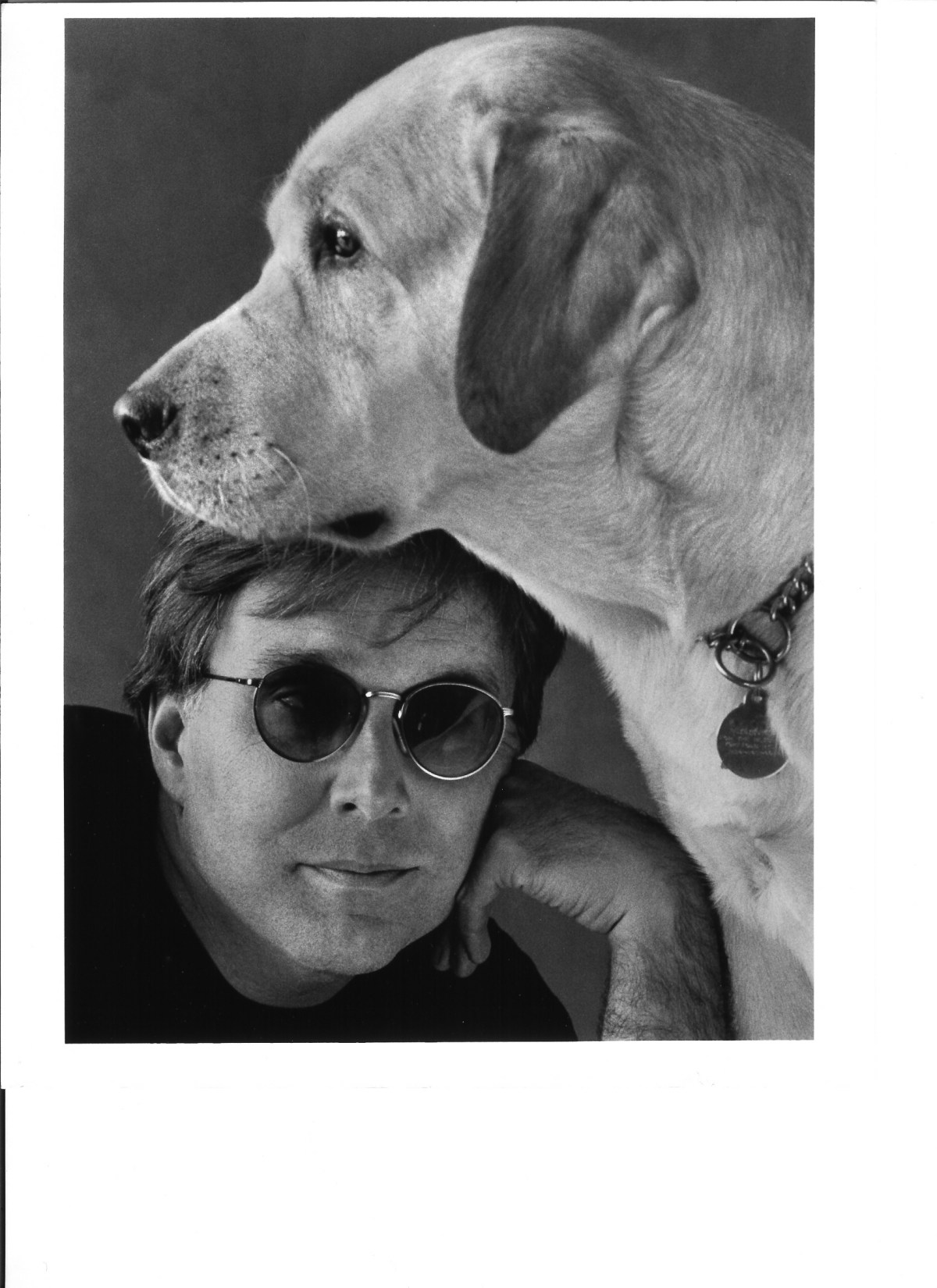

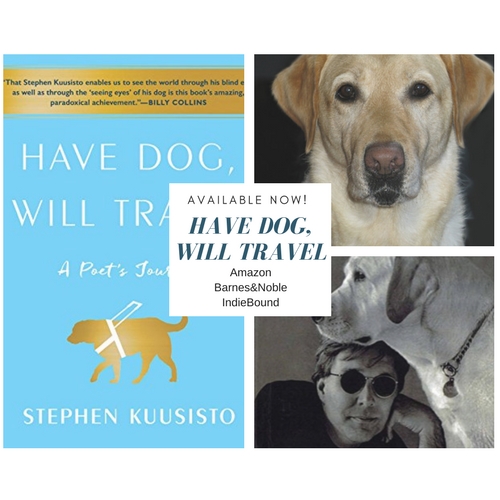

ABOUT: Stephen Kuusisto is the author of the memoirs Have Dog, Will Travel; Planet of the Blind (a New York Times “Notable Book of the Year”); and Eavesdropping: A Memoir of Blindness and Listening and of the poetry collections Only Bread, Only Light and Letters to Borges. A graduate of the Iowa Writer’s Workshop and a Fulbright Scholar, he has taught at the University of Iowa, Hobart and William Smith Colleges, and Ohio State University. He currently teaches at Syracuse University where he holds a University Professorship in Disability Studies. He is a frequent speaker in the US and abroad. His website is StephenKuusisto.com.

ABOUT: Stephen Kuusisto is the author of the memoirs Have Dog, Will Travel; Planet of the Blind (a New York Times “Notable Book of the Year”); and Eavesdropping: A Memoir of Blindness and Listening and of the poetry collections Only Bread, Only Light and Letters to Borges. A graduate of the Iowa Writer’s Workshop and a Fulbright Scholar, he has taught at the University of Iowa, Hobart and William Smith Colleges, and Ohio State University. He currently teaches at Syracuse University where he holds a University Professorship in Disability Studies. He is a frequent speaker in the US and abroad. His website is StephenKuusisto.com.

Have Dog, Will Travel: A Poet’s Journey is now available for pre-order:

Amazon

Barnes and Noble

IndieBound.org

(Photo picturing the cover of Stephen Kuusisto’s new memoir “Have Dog, Will Travel” along with his former guide dogs Nira (top) and Corky, bottom.) Bottom photo by Marion Ettlinger