As we honor the 200th birthday of Walt Whitman it’s worth recalling the poet who praised the human body was also our nation’s first writer of disability memoir. This often surprises people since his great opus “Leaves of Grass” famously celebrates strapping health. In fact one may say Whitman turned physical desire into a sexy religion: America’s body was ecstatic, eternal and spiritually orgasmic. In Walt’s nation there were no bad couplings. That was Whitman circa 1855. Then came the Civil War.

One response to crisis is the making and shaping of a new imaginative body. In his seventies, and having suffered paralysis from a series of strokes, Whitman began collecting, arranging, and then supplementing his civil war prose written while he served as a nurse in the terrible army hospitals in Washington. Revisiting his old journals, their pages literally blood stained, he worked both with his paralysis—he could barely write—while giving shape to a historical moment of national crisis. In effect, Whitman created the first American disability autobiography.

His response to social and personal crises is expertly detailed in a marvelous essay by Robert J. Scholnick entitled, “‘How Dare a Sick Man or an Obedient Man Write Poems?’ Whitman and the Dis-ease of the Perfect Body.” This essay appears in the breakthrough collection, Disability Studies: Enabling the Humanities edited by Sharon L. Snyder, Brenda Jo Brueggemann, and Rosemarie Garland-Thompson.

Scholnick examines Whitman’s early positioning of the healthy body as a metaphor for a strong democracy and shows how the poet used disability to represent political failure as America headed into the Civil War. Referring to Whitman’s unpublished 1856 essay “The Eighteenth Presidency!” Scholnick notes that Whitman is: “Expressing his belief that a healthy body is a metonym for a healthy nation and, the converse, that an enfeebled body reflects a failure within the body politic…” (248). Scholnick correctly observes that Whitman, who is writing about the political failure of the Buchanan presidency to stop the spread of slavery into the western territories resorts to disabling metaphors:

…[Whitman] deployed a rhetoric of health, disease, and disability to address the national crisis. Describing the supposedly enfeebled political class as “blind men, deaf men, pimpled men scarred inside with the vile disorder, gaudy outside with gold chains made from the people’s money,” in “The Eighteenth Presidency!” he summoned what he imagined as a generation of vigorous young men to take charge. “Poem of the Road” (later titled “Song of the Open Road”) warned that “None may come to the trial till he or she bring courage and health” (Leaves 232). (248) Scholnick observes that Whitman’s disabling metaphors are balanced by a call not just to political health in the United States, but also by a prescriptive exhortation to America’s citizens to practice the art of good health:

Whitman’s urgent summons to his fellow citizens to adopt the practices of healthy living constituted a significant portion of his agenda for America. “All comes by the body only health puts you in rapport with the universe,” he wrote in “Poem of Many in One” (later titled “By Blue Ontario’s Shore”). “Produce great persons, the rest follows,” he affirmed (181). “Poem of the Road” stated flatly, “He travelling with me needs the best blood…” and warned that only the healthy are eligible to join him in the great American procession. (249)

Scholnick quotes Whitman in “Poem of the Road:

Come not here if you have already spent the best of yourself! Only those may come who come in sweet and determined bodies, No diseased person no rum- drinker or venereal taint is permitted here. (249)

In turn, Scholnick details Whitman’s reified and “schizoid” body politic:

In promoting physical health as a means of fostering national stability, control, and improvement, Whitman excluded those lacking the best blood. This exclusion raises the question of just how he and his contemporaries understood the etiology of sickness and disability. (249)

Robert Scholnick’s essay explores how the language of Whitman’s later notebooks displays the poet’s alteration from rhetorical inattentiveness about the disabled body to a position of cultural empathy. By ministering to the maimed and dying soldiers, Whitman faced unimaginable physical suffering. The poet’s prose reveals Whitman’s new and profound appreciation for the literal suffering of men and the spiritual suffering of the nation.

I agree with Scholnick that Whitman is the progenitor of the “disability memoir.” He created a new and wholly conscious rendering of altered physicality in prose. Whitman begins his reminiscence (which he called “Specimen Days”) in a wholly new mode. This is not the metaphorized body of the ideologically constructed man of robust, democratic labor:

Specimen Days

A HAPPY HOUR’S COMMAND

Down in the Woods, July 2d, 1882. — If I do it at all I must delay no longer. Incongruous and full of skips and jumps as is that huddle of diary-jottings, war-memoranda of 1862-’65, Nature-notes of 1877-’81, with Western and Canadian observations afterwards, all bundled up and tied by a big string, the resolution and indeed mandate comes to me this day, this hour, — (and what a day! what an hour just passing! the luxury of riant grass and blowing breeze, with all the shows of sun and sky and perfect temperature, never before so filling me body and soul) — to go home, untie the bundle, reel out diary-scraps and memoranda, just as they are, large or small, one after another, into print-pages. (Whitman 689)

This is Whitman, the disabled poet working to shape and re-shape his memories as well as his present circumstances. He does so with fragments, jottings, things untied, things untidy, nature notes, bureaucratic memoranda… He is announcing his intention to create a “lyric collage” –and by announcing that this is for the printed page he is also announcing that this is a work of art, one created out of a new urgency.

Here is Whitman again, writing of his increasing paralysis and its effect on his ways of living:

Quit work at Washington, and moved to Camden, New Jersey — where I have lived since, receiving many buffets and some precious caresses — and now write these lines. Since then, (1874-’91) a long stretch of illness, or half-illness, with occasional lulls. During these latter, have revised and printed over all my books — Bro’t out “November Boughs” — and at intervals leisurely and exploringly travel’d to the Prairie States, the Rocky Mountains, Canada, to New York, to my birthplace in Long Island, and to Boston. But physical disability and the war- paralysis above alluded to have settled upon me more and more, the last year or so. Am now (1891) domicil’d, and have been for some years, in this little old cottage and lot in Mickle Street, Camden, with a house-keeper and man nurse. Bodily I am completely disabled, but still write for publication. I keep generally buoyant spirits, write often as there comes any lull in physical sufferings, get in the sun and down to the river whenever I can, retain fair appetite, assimilation and digestion, sensibilities acute as ever, the strength and volition of my right arm good, eyesight dimming, but brain normal, and retain my heart’s and soul’s unmitigated faith not only in their own original literary plans, but in the essential bulk of American humanity east and west, north and south, city and country, through thick and thin, to the last. Nor must I forget, in conclusion, a special, prayerful, thankful God’s blessing to my dear firm friends and personal helpers, men and women, home and foreign, old and young. (1298)

In lyric terms this prose is necessary to assure the poet’s survival. Gregory Orr’s useful polarities of lyric incitement come to mind: Whitman is experiencing “extremities of subjectivity” as well as the “outer circumstances [of] poverty, suffering, pain, illness, violence, or loss of a loved one.” As Orr points out: “This survival begins when we “translate” our crisis into language–where we give it symbolic expression as an unfolding drama of self and the forces that assail it” (4).

It’s interesting in this context to note that Whitman imagines his paralysis as part of the unfolding drama of family loss as well as the national trauma of the civil war:

1873. — This year lost, by death, my dear dear mother — and, just before, my sister Martha — the two best and sweetest women I have ever seen or known, or ever expect to see. Same year, February, a sudden climax and prostration from paralysis. Had been simmering inside for several years; broke out during those times temporarily, and then went over. But now a serious attack, beyond cure.

Dr. Drinkard, my Washington physician, (and a first-rate one,) said it was the result of too extreme bodily and emotional strain continued at Washington and “down in front,” in 1863, ‘4 and ‘5. I doubt if a heartier, stronger, healthier physique, more balanced upon itself, or more unconscious, more sound, ever lived, from 1835 to ’72. My greatest call (Quaker) to go around and do what I could there in those war-scenes where I had fallen, among the sick and wounded, was, that I seem’d to be so strong and well. (I consider’d myself invulnerable.) But this last attack shatter’d me completely. (1297-1298)

One notes Whitman’s use of military metaphors to describe the onslaught of paralysis: the disease “broke out” and “then went over” –figures that suggest the illness has scaled the healthy wall of his body, the fortress of self. It’s interesting also to note that Whitman arrives at this correspondence between his paralysis and the national trauma of the civil war by way of his doctor who believed that the strain of working in wartime hospitals was the likely cause of Whitman’s stroke.Describing his youthful and healthy body Whitman writes, “I doubt if a heartier, stronger, healthier physique, more balanced upon itself, or more unconscious, more sound, ever lived, from 1835 to ’72” (1297-1298).

By distinction Whitman as the writer of lyric prose is no longer unconscious and balanced but self-conscious and obviously unbalanced. This “imbalance” is reflected by the unevenness of the memoir. Sentences read like fragments. Memories and the contemporary circumstances of the writer are narrated “paratactically” –the past and the present are presented side by side.

One is reminded of the contemporary American poet Gregory Orr’s assertion that:

…our instability is present to us almost daily in our unpredictable moods and the way memories haunt us and fantasies play themselves out at will on our inner mental screens. We are creatures whose volatile inner lives are both mysterious to us and beyond our control. How to respond to the strangeness and unpredictability of our own emotional being? One important answer to this question is the personal lyric, the ‘I’ poem dramatizing inner and outer experience. (4)

In the case of Whitman’s lyric prose this instability links with the art of memory to address the very meaning of the lyric self: the self that possesses comic irony—a self that understands it is a shaped thing. It can be shaped by personal or physical suffering or by social forces. Whitman ends “Specimin Days” by speculating about the divine or philosophical nature of suffering:

Just as disease proves health, and is the other side of it. . . . . . . . . The philosophy of Greece taught normality and the beauty of life. Christianity teaches how to endure illness and death. I have wonder’d whether a third philosophy fusing both, and doing full justice to both, might not be outlined. (1300)

Here Whitman, writing in paralytic bursts, wonders about the construction of normalcy and its origins in stoic philosophy Then in one swift lyric shift, he wonders about the Christian view of illness, a view which leads in Western civilization to the so called “medical model” of disability. This is the “I” of lyric prose, working its way through inner and outer experience. The “I” of lyric prose assembles its greater sense of irony from scraps.

Whitman’s lyric prose is more than the short hand for a self help book. The prose he wrote in crisis lead him away from his early figurative representations of the muscular

democratic body. He wrote in the civil war hospitals on pages stained with the blood of dying soldiers. He wrote fast and he wrote about something larger than ideological metaphor:

FALMOUTH, VA., opposite Fredericksburgh, December 21, 1862. — Begin my visits among the camp hospitals in the army of the Potomac. Spend a good part of the day in a large brick mansion on the banks of the Rappahannock, used as a hospital since the battle — seems to have receiv’d only the worst cases. Outdoors, at the foot of a tree, within ten yards of the front of the house, I notice a heap of amputated feet, legs, arms, hands, &c., a full load for a one-horse cart. Several dead bodies lie near, each cover’d with its brown woolen blanket. In the door-yard, towards the river, are fresh graves, mostly of officers, their names on pieces of barrel-staves or broken boards, stuck in the dirt. (Most of these bodies were subsequently taken up and transported north to their friends.) The large mansion is quite crowded upstairs and down, everything impromptu, no system, all bad enough, but I have no doubt the best that can be done; all the wounds pretty bad, some frightful, the men in their old clothes, unclean and bloody. (712)

In the Preface to Leaves of Grass Whitman wrote, “All beauty comes from beautiful blood and a beautiful brain” (11). As the writer of lyric prose Whitman writes:

I must not let the great hospital at the Patent-office pass away without some mention. A few weeks ago the vast area of the second story of that noblest of Washington buildings was crowded close with rows of sick, badly wounded and dying soldiers. They were placed in three very large apartments. I went there many times. It was a strange, solemn, and, with all its features of suffering and death, a sort of fascinating sight. I go sometimes at night to soothe and relieve particular cases. Two of the immense apartments are fill’d with high and ponderous glass cases, crowded with models in miniature of every kind of utensil, machine or invention, it ever enter’d into the mind of man to conceive; and with curiosities and foreign presents. Between these cases are lateral openings, perhaps eight feet wide and quite deep, and in these were placed the sick, besides a great long double row of them up and down through the middle of the hall. Many of them were very bad cases, wounds and amputations. Then there was a gallery running above the hall in which there were beds also. It was, indeed, a curious scene, especially at night when lit up. The glass cases, the beds, the forms lying there, the gallery above, and the marble pavement under foot — the suffering, and the fortitude to bear it in various degrees — occasionally, from some, the groan that could not be repress’d — sometimes a poor fellow dying, with emaciated face and glassy eye, the nurse by his side, the doctor also there, but no friend, no

relative — such were the sights but lately in the Patent-office. (The wounded have since been removed from there, and it is now vacant again.) (717-718)

Think of Whitman writing after a series of strokes, revisiting his old notebook pages, tying them together with seasoned reflections on his diminished body. By gathering “Specimen Days” and arranging its pages, Whitman claimed disability—both for himself as well as the civil war veterans. Claiming disability requires claiming the lyric. If people with disabilities have been exiled by history, by the architectures of cities and the policies of the state, then the lyric and ironic form of awareness is central to locating a more vital language. The lyric mode is concerned with momentum rather than certainty. This is the gnomon of lyric consciousness: darkness can be navigated. The claiming of disability is the successful transition from static language into the language of momentum. But of particular importance in this instance is the brevity of the lyric impulse. The urgency of short forms reflects the self-awareness of blocked paths and closed systems of language. The lyric reinvents the psychic occasion of that human urgency much as a formal design in prosody will force a poet to achieve new effects in verse. Igor Stravinsky put it this way: “The more constraints one imposes, the more one frees one’s self. And the arbitrariness of the constraint serves only to obtain precision of execution.” We are in a hurry. We must tell the truth about the catastrophe that is human consciousness. And like Emily Dickinson who feared the loss of her eyesight we will tell the truth but “tell it slant”—the lyric writer may not have a sufficiency of time.

Twice then we see Walt Whitman, lacking a sufficiency of time, writing the lyric claim.

Citations:

Orr, Greogry. Poetry As Survival. Athens: The University of Georgia Press, 2002.

Scholnick, Robert J. “‘How Dare a Sick Man or an Obedient Man Write Poems?’ Whitman and the Dis-ease of the Perfect Body.” Disability Studies: Enabling the Humanities. Ed. Sharon L. Snyder, Brenda Jo Brueggemann and Rosemarie Garland-Thomas. New York: The Modern Language Association of America, 2002. 248-259.

Whitman, Walt. Complete Poetry and Collected Prose. Ed. Justin Kaplan. New York: Library of America, 1982.

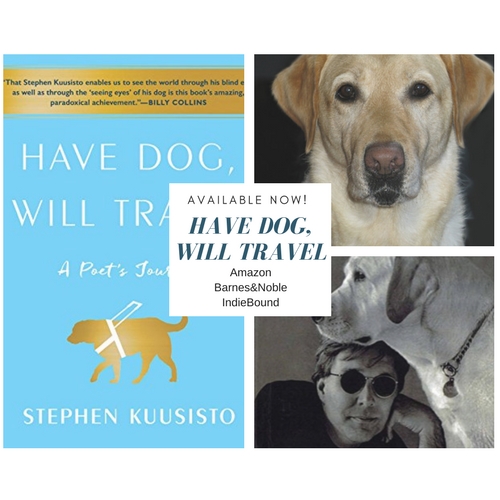

ABOUT: Stephen Kuusisto is the author of the memoirs Have Dog, Will Travel; Planet of the Blind (a New York Times “Notable Book of the Year”); and Eavesdropping: A Memoir of Blindness and Listening and of the poetry collections Only Bread, Only Light and Letters to Borges. A graduate of the Iowa Writer’s Workshop and a Fulbright Scholar, he has taught at the University of Iowa, Hobart and William Smith Colleges, and Ohio State University. He currently teaches at Syracuse University where he holds a University Professorship in Disability Studies. He is a frequent speaker in the US and abroad. His website is StephenKuusisto.com.

ABOUT: Stephen Kuusisto is the author of the memoirs Have Dog, Will Travel; Planet of the Blind (a New York Times “Notable Book of the Year”); and Eavesdropping: A Memoir of Blindness and Listening and of the poetry collections Only Bread, Only Light and Letters to Borges. A graduate of the Iowa Writer’s Workshop and a Fulbright Scholar, he has taught at the University of Iowa, Hobart and William Smith Colleges, and Ohio State University. He currently teaches at Syracuse University where he holds a University Professorship in Disability Studies. He is a frequent speaker in the US and abroad. His website is StephenKuusisto.com.

Have Dog, Will Travel: A Poet’s Journey is now available for pre-order:

Amazon

Barnes and Noble

IndieBound.org

(Photo picturing the cover of Stephen Kuusisto’s new memoir “Have Dog, Will Travel” along with his former guide dogs Nira (top) and Corky, bottom.) Bottom photo by Marion Ettlinger

One thought on “The Original American Good Man: Walt Whitman Discovers Disability”