Two nights ago I over drinks and dinner with poets and writers at the University of Cincinnati I let my disability freak flag fly. Sometimes (though I aim to be circumspect and polite, especially with new found friends) I feel the distress of disablement–the peninsula effect of the matter—my people are the last people to be surveyed, especially in academic circles. While some American universities have disability studies programs or courses the majority of colleges do not. Moreover, while diversity gets discussed in neoliberal circles within higher education these discussions usually leave the disabled out. I admitted the following things to the poet Rebecca Lindenberg one of my hosts:

I’m 63 years old and still fighting for disability inclusion everywhere. The fight often seems to be going badly, or backward.

As I age I feel the pull of the soul—really, those roads of the guitar as Lorca might say. I don’t want to die angry. While I don’t expect to vanish tomorrow, I could. I cross the streets with a guide dog. I navigate on faith. The unseen is very present in my daly thoughts.

I’m tired of the academic creative writing industry with its conferences that are often hostile to disabled participants. With academic literature programs that foreground the notion of intersectionality but still leave disability out of discussions of hegemony and oppression.

I told Rebecca how disheartened many of us are in the disability community (which is hardly monolithic) by the steep struggle we still face to be recognized by feminist scholars, LGBTQ scholars, African-American scholars, and so forth.

Such things aren’t on my mind as exercises. This summer at the famous MacDowell Colony for the Arts I heard a famous novelist tell a huge crowd that the MacDowell Colony would no longer be blind and poor when it comes to recognizing comic novels as an art form. He then repeated the phrase because he thought it was so apt. And there I was, sitting on a folding chair with my guide dog. Disability as metaphor is used by artists and progressives all the time. This hurts. No wonder the Association of Writers and Writing Programs conference remains indifferent and even rude to disabled writers. Everyone knows there’s something wrong with us beyond the obvious.

I talked about the war on disability that’s underway because of genetic research and the movement to eliminate disabled bodies which comes from both the scientific community—eugenics 2.0—and political persuasions—Iceland has eliminated people with Down syndrome for example. Hitler called the disabled “useless eaters” and we’re still imagined that way by the political state, even European states.

I rattled on and on, letting out my frustrations. I talked about academic creative writers who have disabilities and pretend they don’t and how much this disturbs me.

I know I was venting in good company for Rebecca Lindenberg has her own disability and struggles with it hourly.

And there’s the specter of Trumpism, being triggered, feeling a neurological highjacking going on all the time, a fight or flee distress because deviant bodies are under attack.

And so it occurred to me Rebecca snd I might start a very informal back and forth dialogue to which we can invite others here on this blog. What is just anger for writers? How do we build bridges? Or as the poet James Tate once said, “start a fire with our identification papers.?

—Stephen Kuusisto

Rebecca Lindenberg responds:

Thank you so much for sharing the note above with me. I think it captures the breadth of our conversation aptly, though I think it’s worth mentioning (in the spirit of candor) how emotionally charged such conversation can be, though I think of that as a positive thing. Sometimes I wonder how much of the American conversation would be different if we were all a little more willing to be uncomfortable for the sake of someone else, to push our own envelopes more. To wrestle with the difficult. Because for me, part of the defining characteristic of living with chronic disease and disability is learning to persist with difficulty, to muddle through what you cannot get “over” or around, to sit with uncomfortable realities, and also, learn to problem-solve them. Problems, I find, are easier to solve in collaboration than alone, pretty much every time. But you can’t solve a problem that one of your collaborative group does not acknowledge or understand. The bravery to be candid, and also the courage to hear what is candidly spoken, are two kinds of strength that the world requires of us if we’re to make it any better.

I’ve thought about this a great deal. I remember one evening, many years ago, after a sort of semi-official writerly function where my late partner Craig had been (it seemed to me at the time) somewhat bracingly frank with our hosts, I sort of wearily admonished him for acting like kind of a jerk. And I’ll never forget his response, because it was: “Do you want me to be Good, or do you want me to be Nice?” I remember my initial thought was, Why can’t you be both? But years on, I think more and more every day that it is too often difficult to be both. And while I very much want people to like me, as I think most socialized humans do, when push comes to shove, I’d rather be Good. By “good” in this context, I mean just. I mean compassionate and humane, but also unafraid to advocate for myself, for my trans daughter, for my students, and so forth. I also mean fair, and mindful of others, and cognizant of complexities, and insofar as I am able, conscious of my own positions of privilege and my own gaps of knowledge and understanding. As we were talking about together the other night, I do not think candor is opposed to kindness, and I do not think “politeness” is particularly healthy – in fact I think it’s a coercive and often insidious way of keeping people “in line” who might otherwise disrupt the status quo from which the mighty (pretty much singularly) benefit. And politeness insists that those in charge not be made uncomfortable. But if they (or in some cases, we) do not feel uncomfortable, how can they (or we) come to know that something is very, very wrong? And along those lines, I believe that anger is a very important emotion, and a healthy one. (I was joking about this on social media the other day, actually, a beloved friend of mine responded to one of my posts with “Anger is healthy,” and I replied in all caps, “THEN I AM FULL OF HEALTH,” which is especially ironic for me, and for the sources of my anger.) But it’s true – anger is a source of energy, of activity, and of agency. Anger empowers. But anger should never, ever be confused with abuse. Abuse does not empower, it silences, it paralyzes. And it is designed to silence and paralyze. And it can come from any of us, at any time. Anger is interested in getting things going the right way, abuse is only interested in getting its own way. And at almost any cost. But because anger – and I almost feel Blakean about its “infernal energy” – has so much to offer, we do sometimes have to put politeness away in its favor. Because the one thing politeness is designed to avoid, really, is anger. Here’s a joke to show you what I mean:

Two Southern Belles are sitting on a porch, rocking in their rocking chairs, fanning themselves with their fans. Southern Belle #1 turns to Southern Belle #2 and says (you have to imagine your best high-falutin’ Southern drawl here):

Do you see that horse out there? My daddy bought me that horse because he loves me so much.

Southern Belle #2 says: That’s nice.

Southern Belle #1 says: Do you see that grand house over yonder? My daddy bought

me that house because he loves me soooo very much.

Southern Belle #2 says: That’s nice.

Southern Belle #1 says: See that there shiny auto-mobile? My daddy bought me that auto-mobile because he loves me so much.

Southern Belle #2 says: That’s nice.

Southern Belle #1 says: What’s your daddy done for you lately?

Southern Belle #2 says: He sent me to a finishing school in Switzerland.

Southern Belle #1 says: What’s finishing school?

Southern Belle #2 sighs, folds her fan in her lap and says: It’s a boarding school for young ladies, where you learn such things as proper deportment, and elocution, and which spoon to serve with which kind of soup, and how – when you really, really want to say Go Fuck Yourself – you say, ‘That’s Nice’.

It’s funny, that joke, but it kind of gets at the point I’m trying to make, nonetheless. “Politeness” is – by its very design – repressive. And that joke is funny because, as they say, nobody died. But it’s not always so amusing.

Now, to clarify a little, I’m all in favor of being considerate of those around you, their feelings and experiences. I think it was Lucille Clifton who once said (not wrote, she just came out and said it), “Walk into any given room, and every single person in that room is going through something you could not even begin to comprehend.” And I think I try to walk into every room mindful of that truth – a truth I have found bears out again and again and again. But “politeness” as we have socially constructed it (a system of “do’s” and “don’ts” like “never talk about sex, politics, or religion,” a nearly-invisible way of propping up a social hierarchy that rewards conformity and punishes difference) isn’t really about being kind or compassionate to people, actually. It’s about asking people, often the most vulnerable people in any given setting, to suffer their own discomfort for the sake of the comfort of whomever in that setting is perceived to have the power or the authority. A man might make a move on a woman, which might make her uncomfortable. Rather than react appropriately (that is, angrily) she will very often downplay the situation, or try to laugh it off and smooth it over, or feel compelled to “let him down easy” so as to “not make a scene,” but that’s more about preserving his dignity than it is about protecting her own. (I should know, I’ve been there, and beaten myself up about it afterwards.) A person of color might find themselves on the receiving end of a rude, racist remark, and instead of calling out the person who made the remark, they might just ignore it, or change the subject, or find a way to gently excuse themselves from the situation. It might be because to correct someone requires more emotional labor than they wish to do at that moment, but one of the reasons it IS emotional labor in the first place is because they’re trying to respond within a code of conversation and behavior that requires certain niceties be observed and maintained, the offending party not be too embarassed, lest (among other things) they somehow retaliate. The implicit threat in coercive politeness is that the person in a position of privilege or power will escalate the situation, if the more vulnerable party does not tow the line. Therefore, being “polite” in a discomforting situation just reminds the individual striving not to “make a scene” or whatever that we don’t really feel safe. Our safety is as fragile as this pretense, which we are primarily called upon to maintain. And people with disabilities are frequently – no, constantly – coerced by this unspoken, culturally-ubiquitous code of “politeness” and asked to hide, downplay, apologize for, or try to compensate for our disabilities. I’m diabetic and I have some of the unfortunate visual complications of my disease (in part because for so long I had no access to meaningful health care, but that’s a whole other story). I have been diabetic for 30 years, or three-quarters of my life, and I can’t tell you the number of times I’ve sneaked off into bathrooms to test my blood sugar secretly in the stall rather than at a table in a restaurant where I might make someone uncomfortable, or the number of times I’ve apologized for having to interrrupt a conversation or shared experience with someone in order to treat a low blood sugar (a situation which, untreated, can be fatal). At some point I caught myself out. Why, I wondered, am I apologizing to this person for trying to keep myself alive? When for a time I couldn’t drive because of hemorrhaging in my eyes, I found myself being excessively obsequious to my Uber drivers, conscious as I was that without them my mobility around a city with really crappy public transportation was very, very limited. So even when I found myself appalled by an assertion about American politics, or a story about a drunk female passenger, or rudeness offered to me personally, I was meek, ameliorating, polite. And it hurt more than I cared to admit to myself, as I became increasingly aware that I was pandering to people I knew were in the wrong, because I also knew that in that situation, I was somewhat frighteningly dependent upon them. Because I felt vulnerable, I tacitly agreed to stroke the egos and protect the dignities of the people who were making me feel my own vulnerability even more. A wound, the salt.

But beyond that, my real beef with coercive politeness is that it inhibits open, honest conversation. Like this one! Like the ones we got a chance to share in Cincinnati. Open, honest conversation can be bracing – for everyone. But I think of that feeling I get from such a conversation – which is a little like being together in a tiny boat at sea – seems to me to represent the feeling of going-through-something with someone else, its own kind of solidarity. It is for me, too, the feeling of growing as a person and a thinker, of pushing my own envelope a little, placing myself in a scenario that would feel, if not for the good intentions of my interlocutor, precarious. It’s work, for sure. But I’d rather do that work than the work of self-censoring, beating myself up, coping endlessly with feelings of awkwardness and discomfort – my own, or yours.

I would be so interested in hearing your further thoughts on these things, and I would be so, so very interested in hearing the thoughts of others, which I expect might be very different from my own, and I would welcome that. It’s my experience that I have had plenty of occasions in my life to think about the things that make my life very, very hard to live sometimes. I know that someone whose life is made hard to live by a different set of circumstances would almost certainly have a different take on things – perhaps expanding upon this conversation, or problematizing some of what I’ve offered. For me, my obsession with literature stems in no small part from my infinite fascination in hearing from others about experiences and points of view that differ from (and also re-contextualize for me) my own.

I wonder who else we could invite to join our conversation? Should we just reach out an invite people? Run it up the flagpole, as it were?

I look forward to our continued correspondence. And I totally forgot to have you sign your book for me so: Next time?

Very warmly,

Rebecca

**

Dear readers, especially poets and writers (though you needn’t hail from this territory alone) please feel welcome to chime in.

You can send me your thoughts and I will post them.

Stephen Kuusisto

stevekuusisto@gmail.com

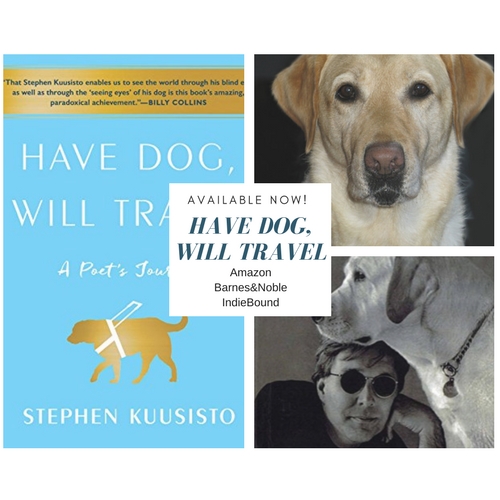

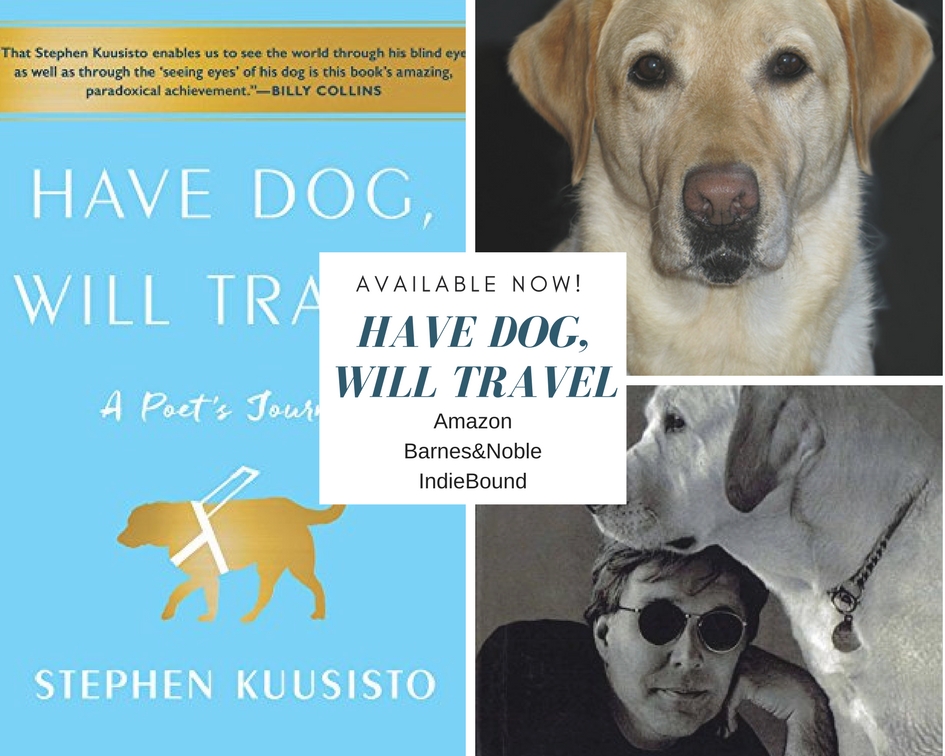

ABOUT: Stephen Kuusisto is the author of the memoirs Have Dog, Will Travel; Planet of the Blind (a New York Times “Notable Book of the Year”); and Eavesdropping: A Memoir of Blindness and Listening and of the poetry collections Only Bread, Only Light and Letters to Borges. A graduate of the Iowa Writer’s Workshop and a Fulbright Scholar, he has taught at the University of Iowa, Hobart and William Smith Colleges, and Ohio State University. He currently teaches at Syracuse University where he holds a University Professorship in Disability Studies. He is a frequent speaker in the US and abroad. His website is StephenKuusisto.com.

ABOUT: Stephen Kuusisto is the author of the memoirs Have Dog, Will Travel; Planet of the Blind (a New York Times “Notable Book of the Year”); and Eavesdropping: A Memoir of Blindness and Listening and of the poetry collections Only Bread, Only Light and Letters to Borges. A graduate of the Iowa Writer’s Workshop and a Fulbright Scholar, he has taught at the University of Iowa, Hobart and William Smith Colleges, and Ohio State University. He currently teaches at Syracuse University where he holds a University Professorship in Disability Studies. He is a frequent speaker in the US and abroad. His website is StephenKuusisto.com.

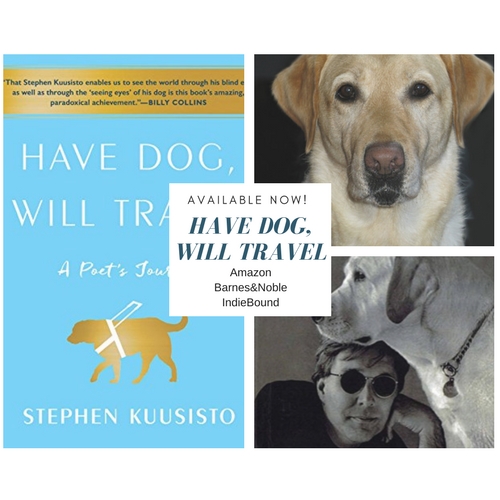

Have Dog, Will Travel: A Poet’s Journey is now available for pre-order:

Amazon

Barnes and Noble

IndieBound.org

(Photo picturing the cover of Stephen Kuusisto’s new memoir “Have Dog, Will Travel” along with his former guide dogs Nira (top) and Corky, bottom.) Bottom photo by Marion Ettlinger

ABOUT: Stephen Kuusisto is the author of the memoirs Have Dog, Will Travel; Planet of the Blind (a New York Times “Notable Book of the Year”); and Eavesdropping: A Memoir of Blindness and Listening and of the poetry collections Only Bread, Only Light and Letters to Borges. A graduate of the Iowa Writer’s Workshop and a Fulbright Scholar, he has taught at the University of Iowa, Hobart and William Smith Colleges, and Ohio State University. He currently teaches at Syracuse University where he holds a University Professorship in Disability Studies. He is a frequent speaker in the US and abroad. His website is StephenKuusisto.com.

ABOUT: Stephen Kuusisto is the author of the memoirs Have Dog, Will Travel; Planet of the Blind (a New York Times “Notable Book of the Year”); and Eavesdropping: A Memoir of Blindness and Listening and of the poetry collections Only Bread, Only Light and Letters to Borges. A graduate of the Iowa Writer’s Workshop and a Fulbright Scholar, he has taught at the University of Iowa, Hobart and William Smith Colleges, and Ohio State University. He currently teaches at Syracuse University where he holds a University Professorship in Disability Studies. He is a frequent speaker in the US and abroad. His website is StephenKuusisto.com.