“With” a disability has always struck me as a very odd expression as the preposition is transformed by it’s company. A bottle of claret with your steak; a scissors with the paper, each conveys a cathected, sub-transitive eidon; “with” is in tandem, in situ, and peradventure going nowhere, for though the wine may be drunk and the paper sliced “with” is obedient. Static. It remains so in social terms—“she’s with him; they’re with the team; it assumes a giving away. He’s a fan because he’s with the team. Your personhood goes nowhere save in concert with the Yankees.

“With” disability strains the preposition, twists it like a spine with scoliosis because disablement is, no matter what many may think, never static. Since disability is never fixed or steady the preposition is tacitly broken—a woman is not with her multiple sclerosis but instead must, necessarily have a phenomenological experience of it—enact it, inspirit, intention it, and thereby make it artful. Disability is, as the phenomenologists say, “categorical intuition” and there cannot be a “with” where escape enjoys primacy.

Person first language is faulty because it’s reliance on prepositions is so entirely imprecise. Ezra Pound once said something like “the poet is the antennae of the race” which as a figure suggests the imagination is intuitive, probative, and out ahead of the culture. I am ahead of my disability, not with it. This is disability as phenomenological and intellectual action.

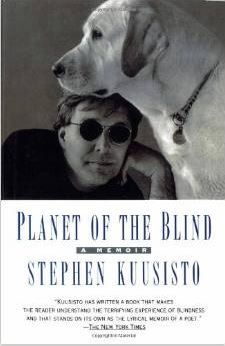

In my forthcoming book about the art of living and working with a guide dog I write about precisely this awareness…

We talk about the art of getting naked or of flower arranging, but we never speak of the art of becoming disabled. In America disability is discussed simply as rehabilitation, as if living is no more complicated than lighting a stove.

The art of getting disabled is a necessary subject. When we look to history we find examples of this art everywhere. Disabled makers stand against loss. They make something of difference. When traveling in France Thomas Jefferson broke his wrist. A surgeon set the break badly. A major facet of his life was changed forever. He was forced to put aside his treasured violin. In turn he took up long, slow, leisurely horseback rides as a meditative practice.

Blind people don’t necessarily need dogs. White cane travel is a very fine way to get around. But I say guide dog travel is an art. It’s a means toward living much as Jefferson learned to live. Moving in consort with an animal is one way to make a life. Art is mysterious. Some find a path to a certain form. Some find an unlike form.

Thomas Jefferson sang to his horses. He was very fond of singing. Moving in consort requires it I think.

It’s hard to imagine singing to a white cane.

I sang all kinds of things to Corky. For her the singing meant contentment. Often I went into my bad operatic mode and sang Neapolitan love songs to her. Cardilo’s “Core N’grato” was one of my repeated offenses:

Catarí, Catarí, pecché me dici

sti parole amare;

pecché me parle e ‘o core me turmiente,

Catari?

The Great Caruso I was not. I reckon the sight of a man with sunglasses singing in bad Italian to a harnessed dog may well have been amusing to many.

**

Do you need to sing to live well? No. I’ve a great good friend who is nonspeaking. But in turn his whole body is music.

My deaf friends sing.

Many of my wheelchair pals are dancers.

Several of my disabled friends are comedians.

We crackle, zip, exhale, inhale, sport with our fingers, flap, jump, pop wheelies, and jingle with harnesses.

Resourceful life is practiced. Sometimes it is silly. Art can and often should be frivolous. With permission from curators at the Museum of Modern Art I was once allowed to spin Marcel DuChamp’s famous wheel, a bicycle fork with front wheel mounted upside-down on a wooden stool. DuChamp was a DaDaist. He made art by placing things side by side that did not formally belong together. A MOMA staff member handed me a pair of latex gloves and I pulled them on and with Corky watching beside me, I reached out and gave DuChamp’s aluminum wheel a spin. “This is the steering wheel of my life,” I thought. Frivolous motion.

I certainly know some blind folks who’d say I’m over the top talking about art in the context of service dog life and to each his own. All I know for sure is what a guide dog can do. Though the stationary wheel of your life seems forever stopped, your dog says give it a turn.

**

I am no more “with” a disability than I am “with” a tire iron. One understands both the preposition and the noun fail to describe anything.