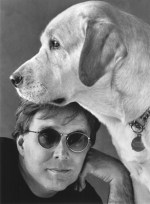

I am a poet who’s blind—I’m also short, dyspeptic, and addicted to savory treats. I feel better for having said so. This is, after all, national poetry month.

Not long ago I attended a writing conference. A poet who has MS said she didn’t want to be a “wheelchair poet” by which (one presumes) she meant she didn't want her writing to be viewed through the lens of disability. Expanding this, I imagine she wouldn't want to be a black poet, a lesbian poet, or a really tall poet. In her view, poetry should be the product of an ex cathedra pronouncement—with a stroke of the pen we can erase all the nagging identity markers of humanity.

Its possible to have a disability and live your life pretending you don’t have one. Plenty of people have done so. But getting away with this charade in literary terms means the imagination has been suborned—bribed—you’ve tricked yourself into thinking there’s a pot of gold that will be yours but only if there isn’t a hint of physical difference in your work. To paraphrase Garrison Keillor: “All the poets are strong, good looking, and above average.”

Forget that our nation’s greatest poet Emily Dickinson had rod-cone dystrophy and couldn’t see in sunlight; forget Walt Whitman’s stroke; ignore bi-polar depression in the case of Theodore Roethke and Robert Lowell; dismiss Alexander Pope’s spinal disease—I’m sorry this is a long list—Sylvia Plath; Hart Crane; Ann Sexton; Allen Ginsberg; William Carlos Williams; forget them all. Disability doesn’t belong in poetry. God help you if you let it in—the critics will dismiss you from the poetry pantheon IN A FLASH since “great” poetry comes from the grandest of all human resources—the dis-embodied mind. (Picture it as a Star Trek arrangement, a brain in a plexiglass case with wires emanating from it.)

When I went to college in the 1970’s English majors were introduced to “New Criticism”—and though this approach to literature was already fading by the time I graduated—poetry world still has a “New Criticism Hangover”. New Criticism argued the study of literature required no knowledge about the writer behind the work. The shaping of words, the wit, the poet’s irony, his literary allusions—these were all you had to know to discern meaning—or as I came to call it—the “soft, chewy center” of a poem.

Back then everyone was still under the sway of T.S. Eliot’s poem “The Wasteland”. We were instructed to read it as a compendium of allusions and to critique it as an allegory of modern exhaustion. No one (and I mean no one) raised his or her hand and said: “Wasn’t Eliot’s wife in a madhouse when he wrote this; and wasn’t he clinically depressed at the time?” We simply talked about the quest for the Holy Grail and the “objective correlative” and, if we were out to impress the prof, we looked up everything in the original Greek.

The New Criticism Hangover stipulates you mustn’t admit your complaining, belching, limping, loudly breathing, dis-articulated, lumbering body into poems. You may only lampoon or parody “other bodies” but this should be reserved for pathos or other symbolic distancing effects.

Many of America’s leading poets do this—blindness represents profound isolation; deafness is simply a metaphor for lack of knowledge; deformity is nothing more than a Grand Guignol effect. If you write like a poet who has NCH you must never hint you have a body of your own.

Of course there are messy feminist poets with their leaking womanly poems; and black poets with their jazzy outrages; but the New Critics Hangover School is uncomfortable with all that stuff.

The “wheelchair poet” remark is part of this heritage—its a highly conscious position—to sequester the outlier body; to keep it in its sarcophagus; to tighten down all the screws.

Me? I’m a messy “wheelchair poet” in the broadest sense. I’m demanding too. I cause trouble in public spaces. I’ll make you move your stone lions if they block the damned sidewalk. I’ll demand you provide me with a trash can at the Hilton so I can pick up my dog’s shit. If you don’t bring me the can, I’ll leave the shit right here. I’m loud. I’m really loud. I like hip-hop. I like Mahler symphonies and I turn them way up. I’m a poet who not only admits the defective body into literature—I think the imagination is starving for what that damned body knows. I happen to be blind. What do I know? I know things like this:

“Only Bread, Only Light”

At times the blind see light,

And that moment is the Sistine ceiling,

Grace among buildings—no one asks

For it, no one asks.

After all, this is solitude,

Daylight’s finger,

Blake’s angel

Parting willow leaves.

I should know better.

Get with the business

Of walking the lovely, satisfied,

Indifferent weather —

Bread baking

On Arthur Avenue

This first warm day of June.

I stand on the corner

For priceless seconds.

Now everything to me falls shadow.”

Excerpt From: Stephen Kuusisto. “Only Bread, Only Light.” iBooks. https://itun.es/us/1017I.l

Did I mention William Blake? He had a disability too.